Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 156

September 25, 2012

It looks better online!

MSW Home

In this Issue:

Two Books on Religion

New Feature! Almost Heaven White-Water Outfitters and Book Club

Announcements and More

Good Reading Online

Free e-mail subscription to this newsletter.

To create a link to this newsletter, use this permanent link .

For Back Issues, click here.

It seems that people are beginning to take a look at the world of the Born Again/ fundamentalist Christians from the inside out. I recently wrote an outside-reader evaluation of a memoir about that world for a publisher, and one of my students in an advanced novel class was writing a novel set among Catholics with a rigid practice that was at once exotic and very familiar to me.

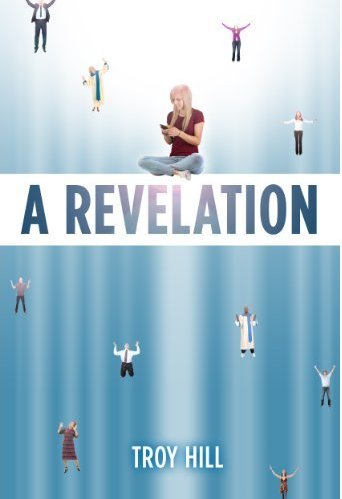

And now here comes Troy Hill's strange and hilarious A REVELATION. Hill is a playwright, poet,

advertising

writer and more who has written a quirky young adult novel with one of

the funniest opening lines I've ever read: "The thing that surprised Dee

the most about the Rapture was the fact that she could still post to

Facebook from her iPhone." The direct voice and simple dramatizing of

what some fundamentalist Protestants believe is going to happen very

soon turns a suburb of the American South into a fantasy world built of

wild imagery drawn from the Book of Revelation in the Christian New

Testament.

advertising

writer and more who has written a quirky young adult novel with one of

the funniest opening lines I've ever read: "The thing that surprised Dee

the most about the Rapture was the fact that she could still post to

Facebook from her iPhone." The direct voice and simple dramatizing of

what some fundamentalist Protestants believe is going to happen very

soon turns a suburb of the American South into a fantasy world built of

wild imagery drawn from the Book of Revelation in the Christian New

Testament.The story is told by a friendly, everyday, super-contemporary girl to whom the Rapture and end times unfold just as she was taught they would. The whoosh up to Heaven and the battle with the Antichrist don't stir her family as much as the fact that she falls in love with a Muslim boy. The lovers are funny and realistic in how they are separated by their different expectations. Aazim is a nerd with a good body and far more romantic than Dee, who is feisty and brave and stands up for the outsider. The first half of the book is all teen age struggles with cultural differences in an atmosphere of xenophobic suspicion.

In order to communicate with Dee, Aazim trains himself to write English in Face Book shorthand (I Lv U 4ever). Dee, who knows she shouldn't love someone who hasn't accepted Jesus Christ as his Personal Lord and Savior tries to play the field, but keeps turning back to Aazim. Both sets of parents, needless to say, want to throw obstacles in the path of love.

The second half of the book is something else again. Matter-of-factly, as experienced by Dee, we see angels, The Lord, and all sorts of beings described in the Book of Revelation. Scholars have a lot of interesting things to stay about the Biblical Revelation, by the way– mainly that it was never meant to predict the future and is probably about Emperor Nero and the Roman Empire. For Dee and her family, however, this is a script for the future, which is how Troy Hill plays it in the second half of the novel. There are beasts, there are terrible tribulations on earth. Dee gets to be an assistant to an angel named Sheeba and open the gates of the Fiery Pit. (Dee is qualified to do this because she's still a virgin-- Angel Sheeba apparently isn't eligible herself). Towards the end, after several confusing (but Biblically accurate) Battles and Beasts and 666 stamps on your choice of forehead or hand– Dee finally shouts that it is all Unfair, and switches sides.

I would have liked more of the Pre-Rapture story: the fundamentalist girl and Muslim boy falling in love. Still, the mixing of iPhones and Fiery Pits and the creatures with eyes all over their wings is brilliantly done and unlike anything I've ever read before. Give give this one a try–especially if you like to see ideas carried to their logical and entertaining extremities.

If you don't care for apocalyptic fantasy, try Donna Meredith's touching THE GLASS MADONNA. This story is set mostly in the mid twentieth century among families who worked the vast glass factories in north central West Virginia. Much of the book takes place in the small city that had the hospital where I was born, Clarksburg. It is the story of a family, and a young woman, particularly that young woman's attempt to make a marriage work and then to move on when it does not. Sarah's husband turns out to be abusive, but she is stronger than she

knows.

She is an excellent character, smart but ashamed of her sexuality and

overly concerned about having lost her virginity our of wedlock. Still

this was appropriate to the time and place. Everyone around her seems

to be equally caught up in the fetish of virginity.

knows.

She is an excellent character, smart but ashamed of her sexuality and

overly concerned about having lost her virginity our of wedlock. Still

this was appropriate to the time and place. Everyone around her seems

to be equally caught up in the fetish of virginity.One of the best things about the novel is that we know Sarah has many talents and is ambitious and loving– but it doesn't stop her from getting in a hole. And, even more important, getting in a hole isn't the end of her life. Much of the novel is about how she slowly, and with help, climbs out again. One support comes from her father, an alcoholic, who manages to pull himself together at important junctures.

There is a mystery about who Sarah's grandmother is, and some cross-cut stories from the past about the grandmother and others, as well as some passages from her husband's point of view. In the end, though, it is Sarah's story: her mistakes, her determination, and her passion for the traditionally male-only profession of glass blowing. One of the great assets of this novel is the information and sense of work life that it brings to us: life in the glass factories, but also Sarah's discovery of her talent as a teacher. In the end, she becomes an independent woman, and finds a way to practice her art as well.

Look also for Donna Meredith's new nonfiction book, MAGIC IN THE MOUNTAINS: THE AMAZING STORY OF CAMEO GLASS, and her earlier novel THE COLOR OF LIES at her website, http://www.donnameredith.com.

MORE NOTES ON RECENT READING

I've just finished James Wood's book HOW FICTION WORKS, one of f a handful of excellent books that I've  used

over my life as a guide to reading and a point of departure for

thinking about writing. My earliest, which I read shortly before I

went off to college, was John Ciardi's HOW DOES A POEM MEAN.

used

over my life as a guide to reading and a point of departure for

thinking about writing. My earliest, which I read shortly before I

went off to college, was John Ciardi's HOW DOES A POEM MEAN.

used

over my life as a guide to reading and a point of departure for

thinking about writing. My earliest, which I read shortly before I

went off to college, was John Ciardi's HOW DOES A POEM MEAN.

used

over my life as a guide to reading and a point of departure for

thinking about writing. My earliest, which I read shortly before I

went off to college, was John Ciardi's HOW DOES A POEM MEAN.

James Wood talks a lot about how Gustave Flaubert

essentially invented the modern novel, so I finally read A SENTIMENTAL

EDUCATION. I found it hard to get into: difficult to identify with

Frederic Moreau (or anyone else), as the entire cast of characters with

one or two minor exceptions is deeply selfish and unappealing. Yet–

here's the real magic-- somewhere towards the last quarter, whether

because I made the big commitment of reading so long, or because there

was some critical mass of Flaubert's accumulation of detail and the

recurrence of all those people (always with a slightly new angle, a

slight refraction of light), I was suddenly caring for the wasted lives

and sadness of change. The novel which began random and frivolous had

become rich and resonant. How did Flaubert make that happen? What if I

hadn't known this was a classic? Would I have kept reading?

Also in the nineteenth century mood, I reread George

Eliot's SCENES FROM CLERICAL LIFE, her very first published fiction.

She was not a beginning writer, only a beginning fiction writer, and

these stories show her moving toward the novel, her  real

form. In the longest story, "Janet's Repentance," we have the first of

Eliot's tall, dark haired, intelligent but flawed women. Janet yearns

to be active in the world, but lets a brutal husband drag her into

alcoholism.

real

form. In the longest story, "Janet's Repentance," we have the first of

Eliot's tall, dark haired, intelligent but flawed women. Janet yearns

to be active in the world, but lets a brutal husband drag her into

alcoholism.

real

form. In the longest story, "Janet's Repentance," we have the first of

Eliot's tall, dark haired, intelligent but flawed women. Janet yearns

to be active in the world, but lets a brutal husband drag her into

alcoholism.

real

form. In the longest story, "Janet's Repentance," we have the first of

Eliot's tall, dark haired, intelligent but flawed women. Janet yearns

to be active in the world, but lets a brutal husband drag her into

alcoholism.

The clerics in the stories are mostly admirable in

different ways, especially Mr. Gilfil, who isn't very pious, but had a

great love, and Mr.Tryan who is evangelical and sweet but morbidly

self-sacrificing because of a bad act in his youth.

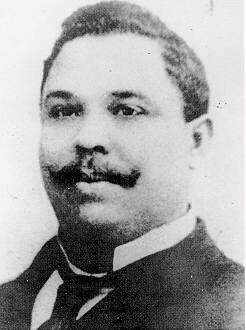

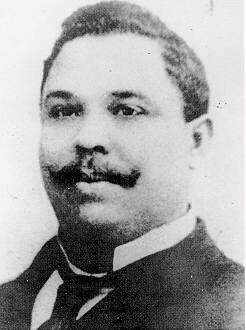

Then, from the very end of the nineteenth century, I

read J. McHenry Jones' HEARTS OF GOLD, brought to my attention by

Phyllis Moore in Issue 131 of this newsletter. This is the one published novel of a man  who

was a college president and extremely active in education and

fraternal organizations-- someone who is not primarily a novelist. It

has some amateurish writing and some wildly melodramatic scenes, but

other parts are breathtakingly good.

who

was a college president and extremely active in education and

fraternal organizations-- someone who is not primarily a novelist. It

has some amateurish writing and some wildly melodramatic scenes, but

other parts are breathtakingly good.

who

was a college president and extremely active in education and

fraternal organizations-- someone who is not primarily a novelist. It

has some amateurish writing and some wildly melodramatic scenes, but

other parts are breathtakingly good.

who

was a college president and extremely active in education and

fraternal organizations-- someone who is not primarily a novelist. It

has some amateurish writing and some wildly melodramatic scenes, but

other parts are breathtakingly good.

Jones himself and his major characters are all

members of the educated elite of African Americans of their time.

Jones shows off the clever repartee of young doctors and journalists

and teachers, and some of it grates on the ear, but there are also many

scenes that pop off the page– the description of a lynching, for

example, without flourishes and flowery language, and the description of

the horrific convict lease mines, which were a privatization of

convict labor after Reconstruction that in many ways circumvented the

abolition of slavery and was a precursor of our present prison system

with its vast holding of young black men.

Above all, Jones writes with conviction. He is

proud of his upper class "Afro-Americans;" he grants his women

characters a lot of energy and self-reliance; he creates a satisfyingly

white villain who seriously considers marrying a mixed race woman to

get her inheritance– but decides instead to kidnap her friend and to

forge a will. This ubiquitous character is at the heart of much of

the melodrama, but he also functions as an emblem of the pervasive

animus of white people toward the struggling blacks.

I enjoyed and recommend this book from West Virginia University Press 's

African American project. It is not high literature (Flaubert would

probably sniff at it), but it is a vital hybrid of idealism, love story,

melodrama, and some brutal facts about African-American life after the

end of Reconstruction.

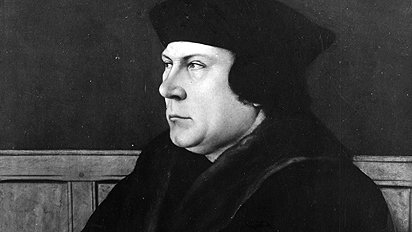

Finally, just to prove that I also read contemporary

books (although this one is set in the court of Henry VIII!), I read

BRING UP THE BODIES by Hilary Mantel. This novel continues her portrait

of Thomas Cromwell and the Court of Henry VIII, begun in WOLF HALL (see

notes in Issue 142)

and tells how he manufactured the court case necessary to have Anne

Boleyn (and a number of others) beheaded. Cromwell does this in

pragmatic service to the King, but he is also also perhaps taking

revenge for the downfall of his mentor, Cardinal Wolsey.  He plays a brutal and deadly game with more enthusiasm that we might like.

He plays a brutal and deadly game with more enthusiasm that we might like.

He plays a brutal and deadly game with more enthusiasm that we might like.

He plays a brutal and deadly game with more enthusiasm that we might like.

I read an online review of it in the NEW YORKER (by James Wood,

mentioned above) that was admiring, but found that Cromwell's thinking

process to be anachronistic because it seemed too real. Wood's example

is Cromwell thinking about his son, and listing his qualities. Wood

sees this as something modern-- to detail one's child's qualities.

But it reminded me of a passage in a Michel de Montaigne's essay in

which he lists his own qualities, bad and good, and Montaigne, of

course, was a rough contemporary of Cromwell.

SOMETHING DIFFERENT: TWO BOOKS ON RELIGION

Joel Weinberger reviews THE ESSENTIAL TALMUD by Adin Steinsaltz and PERMISSION TO BELIEVE by Lawrence Keleen: "[THE ESSENTIAL TALMUD] was a solid intro to the structure and thought process of the Talmud. I started reading this because I've started doing 'Daf Yomi,' reading a page of Talmud a day, and this has been a good jump start in understanding what I'm reading. A lot of the really good stuff is the contextual information about the Talmud. While the tractates themselves are fairly straightforward as to their content,THE ESSENTIAL gives a great historical and religious context for what the Talmud is, where it came from, and why it's important."A note on the author and his style: Steinsaltz is considered one of the absolute great modern Talmud scholars, and is definitely a religious figure. Thus, there is inevitably a religious view on the Talmud within the book. However, the book is about as objective as you could hope, given that it is a religious text. While the author makes assumptions at times, and certainly shows a reverent awe for the Talmud, he also is candid about the historical context and the authors.

"A few relatively minor complaints. Steinsaltz could have provided more examples. He often describe parts of the Talmud, for example how the Sages would tell stories, without providing examples. Similarly, the book could use some deeper explanations such as on the logical techniques of the Gemara.

"A valiant attempt at his goals, but Kelemen falls well short [in PERMISSION TO BELIEVE] from my view. And this is coming from a Believer. To me, chapter 2 is the only chapter that I find truly compelling. In fact, the morality argument is effectively how I came to believe, and Kelemen makes a fine run at the argument. Additionally, chapter 5 on Jewish history as an indicator of the Divine is interesting, but ultimately falls flat."

DREAMA FRISK RECOMMENDS

Dreama Frisk writes to say she is reading something "which is close to having a friend beside me: The Paris Review Interviews vol. 11. There is an introduction by Orphan Pamuk. The interview with Isaac Bashevis Singer particularly strikes me. His belief in his own writing is a model and very down to earth."

THE ALMOST HEAVEN WHITE-WATER OUTFITTERS AND BOOK CLUB READS MARY LEE SETTLE'S O BEULAH LAND

We are beginning a new feature in the Books for Readers Newsletter, which is occasional review discussions from an online book club. They say of themselves: "The Almost Heaven White-Water Outfitters and Book Club is a group of avid readers reluctant to tackle any real West Virginia rapids but eager to dive headlong into the written word, especially words about West Virginia or Appalachia. Periodically, we join via email to discuss our latest choice. As we do, we'll offer our comments, provide a rating, and hope you'll enjoy the ride. In the raft are June Langford Berkley, Charles Lloyd, Eddy Pendarvis, Carter Taylor Seaton, and Phyllis Wilson Moore. Tyler Chadwell and Terry W. McNemar join us occasionally. Each member is from West Virginia and several are authors in their own right."

This month's discussion was Mary Lee Settle's O Beulah Land. Read it here.

No comments:

Post a Comment