"Almost Heaven White Water Rafting Outfitters and Book Club" on William Demby's Beetlecreek

For a Free E-mail subscription to this newsletter:

.

It's been a busy beginning of summer. I just finished teaching an online class with all the interesting work-in-progress that teaches me how prose narrative works. My only problem with these online classes is that, unlike face-to-face teaching, they take

the same sit-at-the-computer energy as writing and putting out newsletters.

So it's been a while since I did #177. However, lucky for me and those of you looking for books to read--I

have a lot of help with reviews. This issue includes a review by the indomitable "Almost Heaven White Water Rafting Outfitters and Book Club" of a novel by the late William Demby set in the city in West Virginia where I was born; a review of Cat Pleska's memoir by Phyllis Wilson Moore; and a hilarious, enthusiastic response to Mitch Levenberg's

Write Something written by Deborah Clearman.

There's a lot more--short reviews and longer. If there's no byline, I wrote it.

William Demby’s Beetlecreek (Review compiled by Eddy Pendarvis from remarks by Almost Heaven White Water Rafting Outfitters and Book Club members June Berkley, Donna Meredith, Phyllis Moore, and guest member Crystal Wilkinson)

Our book club had a particular question about William Demby’s novel, Beetlecreek.

The novel has remained in print for sixty-five years and is cited in many encyclopedias of Black literature. One of our members read the novel years ago and was not impressed by it. On this recent reading, she felt she saw its

merit; but she wondered if her second reading was influenced by the book’s reputation. She posed the question to our club—“Is

Beetlecreek a classic?”

I think it’s fair to say we answered yes. This review summarizes our reasons. The quotes are verbatim opinions of some of the members.

Published in 1950, Beetlecreek has been in print for over half a century. While it doesn’t yet have a strong claim on being a “classic” as a work that has stood up over time, it has a good start in that direction. In representing this microcosm with profound authenticity, it represents a “class” or group of a certain place and time—in this case, people living in the Black community of Glenn Elk, near Clarksburg, West Virginia, in the 1940s. At the same time, it powerfully addresses universal issues.

Beetlecreek “examines the contradictory needs of human beings to belong to a social group and to escape from the constraints of society. Demby applies the theme in a unique way to the black experience and in a particular to blacks isolated in a small community.” The novel is “about alienation of identities and the use of the African American experience as a metaphor for all lives denied dignity in American culture or society in general.”

It’s clear from the first few sentences that this novel is going to be way out of the ordinary. It is a unique coming-of-age story about a Black teenage boy, his uncle, and an old White man. Its depth and honesty in facing the ugliness of reality (and maybe not even seeing it as ugly, but just human) are perhaps the most original things about the book and part of what make it a classic.

Bill Trapp is “the mover of the action.” The only White character who is central to the story, he is an outcast of both the White and Black communities. Trapp has lived as a hermit for years; and in the opening scene, he starts to chase away some Black boys who are stealing apples from his apple tree. One of the boys, Johnny, doesn’t run, and Trapp ends up inviting him to sit down on the porch and have some cider. Not long afterward, Johnny’s uncle David comes by to get his nephew, and the three sit and talk a while longer. With this scene Demby introduces the story’s three main characters, all of whose lives are changed dramatically by the events that come out of their meeting.

An alternative title under which the novel was published at least once is Act of Outrage. And there are outrages of many kinds and at many levels in the story. One of the most obvious is the outrage of racism. Johnny’s uncle, David, says that for him, ‘Negro life was a fishnet, a mosquito net, lace, wrapped round and round, each little thread a pain.’ ” In fact, the back stories of all three protagonists are characterized by the entrapment of poverty and abandonment; but the major outrage in terms of the plot is an imaginary outrage that engenders a real one.

Encouraged by the friendly manner of Johnny and David, Trapp’s conviction to change his life and become part of a community grows. He decides to have a picnic for the local children, both Black and White. Though there appears to be nothing salacious in Trapp’s party plans, an undercurrent of sexuality runs through the story; beginning to end. Demby doesn’t lead the reader much, however, and sexuality as related to children surfaces overtly only in the shack that serves as a clubhouse for a group of teenage boys who live in Beetlecreek. In the privacy of their shack, they look at pornographic pictures and masturbate. Though Johnny is reluctant to join in, his sexuality is part of the story, too.

One of the girls at the party, a girl named “Pokey,” finds a picture of a naked person, tears it out of the book, takes it home, and gets caught with it. The page is from an anatomy book, but she and the adults who see the picture consider Trapp to be a pedophile. In the face of the community’s indignation over Trapp’s supposed imposition on young girls, Johnny and David give in to popular opinion even though they think this opinion is wrong.

The story ends in violence and even greater betrayal, as well as questions about the destiny of all three main characters. Demby’s novel is engaging in its humanity and depth and, maybe most of all in the questions it raises—calling to mind another definition of a literary classic: “a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.”

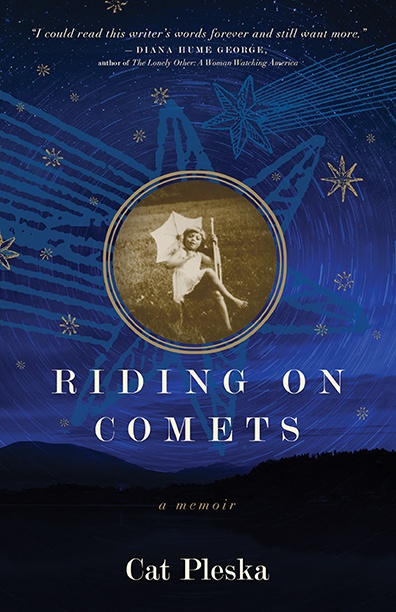

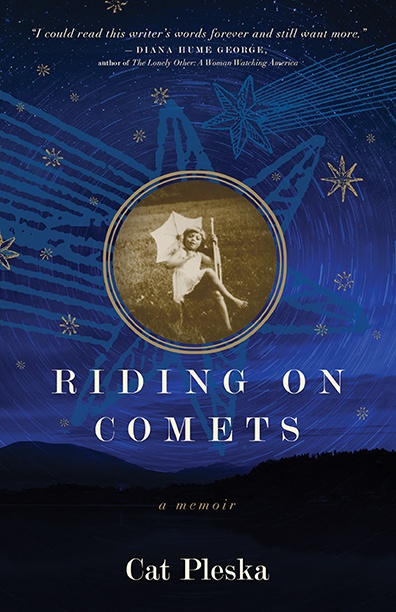

PHYLLIS MOORE REVIEWS CAT PLESKA'S RIDING ON COMETS

RIDING ON COMETS: A MEMOIR by Cat Pleska is as unique as her name. An only child born into a family of story-tellers, Pleska paid attention to the nuances of daily life. Like the proverbial "little pitcher with big ears" Pleska captured the life of her extended family. She didn't always understand

what she heard and saw, but like a camera obscura, she recorded it to ponder.

In RIDING ON COMETS we meet a loving, imperfect, intelligent, working class family. The men drink and smoke too much but hold on to their repetitive jobs. They carouse, hunt, and fight with each other while the women bond and worry about the men and each other. Depression rears its ugly head.

Money is scarce but love isn't.

Little did they know the child in their midst would preserve their lives and share them with the world in a truthful, sometimes humorous way. She recalls their superstitions, folk sayings, and quirky habits. One of the most humorous incidents related in the memoir is told first by the grandfather, then by the father, and finally by the daughter. Each voice is unique and each version has its own flair.

There are poignant chapters about the mundane realities of death: the necessity of buying new underwear for your father or choosing a wig for your mother. Pleska writes about the fears as well as the joys of childhood, about her father's life long curiosity and her mother's love of books. Thankfully, all the monsters under her bed proved imaginary and harmless and she survived to record this legacy of love.

DEBORAH CLEARMAN REVIEWS MITCH LEVENBERG'S WRITE SOMETHING (BRILLIANT, IF YOU CAN!)

Reading Mitch Levenberg fills me with despair. I wish I could write like Mitch Levenberg. In killer two-word sentences. With dark side-splitting humor. I wish I could tell sly WASP jokes the way Mitch Levenberg tells Jewish jokes. I wish I could be Mitch Levenberg.

This reminds me of when I was a young art student and I wanted to be Matisse. But no matter how much I flattened out the nude model into great languorous shapes, no matter how I pared her down to essential sinuous lines, no matter how I surrounded her with decorative fabrics purchased at discount stores on 14th Street, no matter how I tyrannized my classmates putting her into odalisque poses, I couldn't be Matisse. It was 1970, not 1920. Abstract Expressionism had come and gone, the locomotive of art history had roared on to Conceptualism, which I didn't even like, and nobody cared about Matisse any more.

Furthermore, instead of being a fat old genius who lay in bed all day and drew on the walls with his charcoal attached to the end of a long stick, I was an ordinary girl of mediocre talent, who would never change the course of art history, who would have a few shows and a couple children, who would give

up the art world in disgust and start a second career in an equally farfetched endeavor and write a novel that wouldn't be funny and dark like a Mitch Levenberg story but rather just another divorce story. And even my divorce wouldn't have half the existential angst I see in every Mitch Levenberg paragraph. Maybe you have to be Jewish to have angst?

I would never write a sentence as perfect as "he too snores who only sits and waits."

Just a few minutes ago while reading Mitch Levenberg I was struck by the irresistible urge to write about Mitch Levenberg, but first I had to extricate my laptop from under the tray table in the middle seat of a cross-country Jet Blue flight. Perched on the tray table next to my Kindle was of course a cup of hot coffee. Who can read Mitch Levenberg without being filled with a craving for hot coffee? Nearly every other essay in WRITE SOMETHING extolls the power of coffee to raise us to the heights of creativity. In the words of Mitch Levenberg, "I always think coffee. First I think, 'Am I still breathing?' and then I think coffee. Not always in that order." Or how about, "Does it bother me that coffee beans could be extinct by 2080?. . .just the juxtaposition of the words coffee and extinct sends chills down my spine and lethargy spreading throughout my nervous system." Furthermore, "Those two extra cups of coffee every morning provide me with the absolute certainty that I can accomplish anything. . .provide me with the desire to love the world and figure out how to save it all in one streaming heart. .. . "

As I lifted the tray table a mere fraction of an inch and wrestled my laptop out from under my feet, naturally I spilled hot coffee on my lap. This excited the passenger beside me at the window seat, a woman my age who was doubtless familiar with rescuing beverages left in precarious positions by children and grandchildren, and she instinctively swooped in to grab my coffee. Thus further humiliating me after an earlier humiliation when trying to lift my excessively heavy carry-on bag into the overhead bin, I resisted help from a kindly gentleman in the row in front of me and chose instead an elaborate acrobatic feat of climbing onto the armrest of a seat not even my own. When I was still unable to raise my carry-on I finally acquiesced to the offer of help. My embarrassment was increased when I was sure I overheard the passengers in the row in front of me discussing the fact that I had nabbed a spot in the overhead bin that was in fact not my spot. It was a row ahead of my spot. This I had done in an effort to stow my bag in front rather than behind my seat, so that I wouldn't have to wait for the entire plane to unload before retrieving my bag. I was fairly certain they had taken note of this aggressive, or should I say passive/aggressive, move on my part.

And now I will spend the next ten days with coffee stains on my brand new khaki pants.

So I move on to Mitch Levenberg's story "Redemption" because I am feeling in need of some redemption myself and I'm hoping to pick up some wisdom beyond just the wonderful effects of hot coffee. I'm struck by the other half of WRITE SOMETHING, which is not only about writing but is also about the unique writerly experience (Here I must digress. When I was in art school there was a lot of discussion about the word painterly, which we used rather a lot in critiques. What do you mean, painterly, some combative fellow student would ask, probably a sculptor—the sculptors were all conceptual artists at the time. How can you make painter into an adjective? Is there a word sculptorly? Hah! I offer my ripost forty years later in writerly.) the unique writerly experience of reading one's work out loud in front of an audience.

I am struck by Mitch Levenberg's relationship with the act of reading—a love/hate relationship of course—and how it affects his relationships with his stories. How his stories become characters as he presents them to an audience. While I think of my stories as my children—to be nurtured and supported and sent out into the world to stand on their own two feet—Mitch Levenberg thinks of his stories as lovers. He must prove himself worthy of them over and over, and only then will they reward him by delighting and seducing his audience, only then will they redeem him.

Could I redeem myself in the eyes of the woman in the window seat (who has been working on some kind of legal document on her laptop while I discreetly peer over her shoulder trying to figure out what program she's using) by reading her this review of WRITE SOMETHING by Mitch Levenberg?

Or would she find me out as the imposter I am. Now that I have written my own version of a Mitch Levenberg story, I suggest you read the real thing. They're much better.

Keefie by Ken Champion

This novel of the London Blitz splendidly captures real life on the ground mostly through the eyes of a bright and creative working class boy. Young Keith's knowledge of what is going on is limited, but his experience leads

us deep into a time and place– and the lives of ordinary people. Part of what makes the book successful is the narrowness of this slice of reality: Keith painstakingly and with great artistic talent draws the various types of aircraft involved in the bombing and defense of London. He experiences almost nightly interruptions of sleep to go to the bomb shelter.

Otherwise, his life and the lives of his friends are made of family, play, and conflict just like any child's. He has a proud worker father and a middle class-aspirational mother, along with a new baby brother. Life on his street is full of urban games and neighbor kids and a lot of colorful aunts and uncles.

I would have been satisfied to spend the novel in London with these people, hurrying down to the shelters when the air raid sirens go off, going back to bed when the all clear is rung. There's a real beauty to the way the British defiantly continued their lives, the children hardly understanding at all why it was all happening, even a bright, imaginative boy like Keith.

Keith is, however, sent to the countryside for his safety, where he lives with two Americans in a troubled marriage. The male American, Robert, and the third adult in the household, Norman, are professors much given to discussions about sociology and psychology. They focus their attention on the psyche of poor Keith, whose father is perhaps distant and cool, but hardly anything out of the ordinary.

In the end, all the brainy speculations of the adults collapses into the reality of life: Robert begins an affair with one of his students, the brilliant and beautiful daughter of an African diplomat, and Keith, in a misguided burst of racism and a desire to protect his adult friends, attacks her. Meanwhile, the bombs fall in the rural areas, too, and in the end, everyone returns to London– as if that great city were for all of them, not only for Keith, the heart of human struggle.

My Lady Ludlow by Elizabeth Gaskell

I always want to call her "Mrs. Gaskell," which is what she called herself. So does it honor her more to call her what she called herself in 1860 or to call her what honors a woman today? She died at 55, but wrote a load of books, this one called a novella. It was used as part of the material for the BBC production of Cranford.

Like

Cranford, "My Lady Ludlow" has a charming story-upon-story open-ended quality. There's a rather disingenuous narrator, an invalid spinster who spends many years as a ward or guest of the lovely, blatantly reactionary Lady Ludlow. Lady Ludlow is the usually-

benevolent dictator of the small world of this story. Naturally generous, she yet believes that blood and class are fundamental to social order.

The reader's first inkling that her benevolence is associated with some real bad stuff is when she goes off on a rant about how the lower orders should never be educated. Then, as evidence, Lady Ludlow relates a long story-within-the story about the French Reign of Terror and a young aristocrat who escapes to England and is under the protection of her and her husband. He then goes back to France to rescue the cousin he loves, and they are both guillotined. To Lady Ludlow, this tragic romance is supposed to prove how wrong it was for her agent to teach the bright young son of the local poacher to read and write!

The whole book is told with Gaskell's light touch (like Cranfordbut not her "industrial" novels). Bit by bit, Lady Ludlow's old ways are shown up: the young vicar who wants to start a school finally does start one; the poacher's son he taught to read turns out to be a success; an illegitimate girl (Lady Ludlow has always ignored the existence of anyone born out of wedlock) comes to live with one of Lady Ludlow's good friends. And gradually, Lady Ludlow makes her peace with these changes.

Near the end, there is a scene where she entertains for tea a number of people she has pretended didn't exist through much of the story. One ignorant nouveau riche woman with a showy new dress spreads a bandana on her lap to protect her dress from spills. The other ladies titter, and Lady Ludlow proves that truly good breeding is ultimately about kindness: she pulls out her own handkerchief and puts it on her own lap in solidarity with her guest.

I especially like Gaskell's insistence that people can change. Lady Ludlow has been a good-hearted person in many ways from the beginning. She is also a woman who, we learn almost in passing, has lost almost her entire family: all nine of her children die before her. That, I remember was one of my strongest reactions to reading Cranford: how all the silliness and pettiness and small mindedness and comedy is set against a background of constant death from illness and accident.

Ron Rash photographed by Ulf Andersen

JANET MACKENZIE REVIEWS SERENA BY RON RASH

A film has already been made of this novel about naked evil; its distribution held up by concerns over the unrelenting malice of Serena, the main character. Ron Rash, the author uses North Carolina's vulnerable forests as foil to the unbridled ambition of Pemberton's wife. At her husband's logging camp, Serena wears the pants, proud to be the match for any man. Pristine forests are felled by crews desperate for work in the depression. No compensation is paid for loss of life or limb.

A cross between Medea and Lady Macbeth; Serena shows no compassion when men are mangled or killed by logs. Learning she will never bear a child she sets out to kill the son fathered by her husband with Rachel, an orphan. Rash weaves his novel artfully, using the conversation of logging camp workers as a Greek chorus, who comment on Serena's machinations.

Rash's ancillary characters display facets lacking in Pemberton and Serena. Rachel, the resourceful teenage mother of Jacob, Pemberton's unacknowledged son, supports herself and child by working at the logging camp. Her habits of excellence, her woodlore, her desire to be a good mother, her gratitude to a boy who befriends her, create a rounded character. In contrast, the Pembertons are flat; supercilious with workers and dinner guests. Satisfied in and with themselves, their sole ambition is to make pots of money fast.

Pemberton's lumber company owns the town, but can't buy Sheriff McDowell. When a string of deaths occurs around the logging camp McDowell accuses the Pembertons of culpability . His courage facing pathological criminals distinguishes him.

Snipes, one of the loggers, sees himself as an intellectual. His pedantic pronouncements and his inability to answer logical questions, create comic moments. Gallagher, a ghoulish local saved from death by Serena's quick thinking, becomes her henchman.

The novel is unevenly written; with wooden portraits of the two central characters balanced by lovely vignettes of minor characters, and a story line which employs brilliantly conceived murders. That the deaths of the two main characters is more interesting than their lives testifies to Rash's ability to make the reader turn pages.

A FEW SHORTER REVIEWS

The Camomile Lawn by Mary Wesley

Thanks to my excellent reading friends, I keep making wonderful new discoveries. I had never heard of Mary Wesley, who isn't exactly a secret, as there've been at least one television mini-series from her work, but she was new to me. She wrote some children's books, but began writing her adult novels in 1983 when she was 71. From 1982 to 1991, she wrote and delivered seven novels. Check out this

article in The Guardian .

This book is England at the beginning of the Second World War, and during it. Maybe I was in the mood after reading

Keefie above, but all the talk and sophisticated sex was just delightful.

Angels of the Appalachians by Deanna Edens

Angels of the Appalachians by Deanna Edens

This is a short e-book-only of linked stories about two women from southern West Virginia, Ida and Erma. There is also a more contemporary figure, Annie, who is a student in the 1980's and a married woman in the present, who talks to the older women and learns their histories and shares some of their final years.

The big city Ida and Erma go to is Charleston WV, the state capital, where they work their way through college. The small town they come from is Thurmond in the New River valley, a coal and railroad town in its heyday in the early twentieth century.

The background to these stories is a time when men died in the mines with brutal regularity, and the United Mineworkers was just organizing. The kindly Mrs. Jones who helps out the girls' families is a relative of Mary "Mother" Jones, the union organizer and firebrand. The lives of Ida and Erma, as filtered by the much younger Annie, are told with humor and a light touch, emphasizing the happy moments and real life angels of the region.

A Great Deliverance by Elizabeth George

Elizabeth George turns out to be an American, something of a disappointment to me, because my favorite thing about mysteries and thrillers is almost always the setting. I depend on my mystery writers to know their territory. George may know Yorkshire, but not in the way Michael Nava, say, knows gay Los Angeles during the AIDS plague.

So this was fun, but it suffered from soft spots the way a lot of these ripe genre novels too, as if they were missing one last revision. I figured out early that the real crime was going to be the child abuse. The whodunit is subsumed by the crime underlying the mystery.

Death at La Fenice: A Commissario Brunetti Mystery By Donna Leon

This writer is also American author, but she has lived in Venice for decades. I got the idea to read this book from the

"guilty pleasures" list below . Anyhow, I really did like Venice in this mystery, Leon's first, and it got better as it went along. The sleuth, Guido Brunetti, is smart and psychically attractive, spending his day knocking back coffees and glasses of wine and brandy. Sounds like

la dolce vita to me!

This series may become a guilty pleasure for me too.

Brother, I'm Dying by Edwidge Danticat

Edwidge Danticat doesn't need recommendations from me, but she is always a delight to read. This is the story of her two fathers, the personal mixed naturally in with politics. Her family neighborhood in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, is a war zone in this memory piece between gangs and UN troops who shoot first and ask questions later. Meanwhile, there are serious illnesses, separations, lots of characters, and the interestingly loving but slightly withdrawn narrator– it is all so particular, and so universal in its particularity.

Nomads of the Wind : A Natural History of Polynesia by Peter Crawford

This picture book was made to accompany a BBC television documentary from twenty years ago. It is about the flora and fauna and history of the Polynesian people and their voyages from Tahiti (most likely) to the Marquesas, Easter Island, Hawaii, and New Zealand. Not scholarly and very upbeat (you can almost heard the underlying inspirational music as the narration rolls on), it inspired me to reread the parts of Jared DIamond's Collapse about Easter Island and the Pitcairns and other Polynesian Islands where human settlements failed without any help from Western colonialsts.

It made much more sense now, especially with the bright Nomads images in mind.

The Return of the Soldier by Rebecca West

The Return of the Soldier was written when Rebecca West was only 24, and it's only 212 pages long. It is a taut and surprising story centered on three women who love one man. The peripheral but passionate narrator is a poor gentlewoman kept by her wealthy cousins. The plot is simply that the man of the house returns to his wife and adoring cousin from the trenches in World War I France with partial amnesia: He does not remember the last ten years or so, which includes his relationship with his wife. He is still in love with another woman, of a lower social class than his, who is married to someone else. There are some difficulties for me with certain assumptions about class and the beautiful descriptions of landscape are long for our taste today, but it is essentially brilliant and intense, and highly worth reading.

IF YOU'RE GOING TO SAN FRANCISO....

Visit the Glen Park San Francisco Bookstore and Jazz club, Bird and Beckett athttp://www.birdbeckett.com/ . It's located at 653 Chenery Street-- almost any Saturday has something terrific happening in music or literature. I happened to pass by when I was visiting last fall, and Diane Di Prima was reading.

JOHN BIRCH E-READER REPORT: KINDLE VOYAGE IS "PROBABLY THE BEST EVER" E-READER

CNET -- a popular website that publishes reviews, news, articles and blogs about everything hi-tech – has rated the Kindle Voyage e-reader "outstanding," the best of 2015, and "probably the best ever." The Voyage is pretty pricey compared with its competitors at $199, up to $120 more than one of its well-rated competitors. All six of the best rated models offer longer battery life and "a more paperlike reading experience" than the color tablets that have emerged on the market.

The runners-up in CNET's top ratings are:

BEST OVERALL E-READER VALUE: Amazon Kindle Paperwhite Rated: Excellent $119

BEST AD-FREE E-INK READER: Barnes & Noble Nook GlowLight Rated: Excellent $99

BEST BARGAIN E-READER: Amazon Kindle 2014 model Rated: Very Good $79.

BACKCHANNEL REPORT

"Looks really interesting."

READ AND LISTEN ONLINE

The Spring issue of Persimmon Tree is still online, full of powerful poetry from Chana Bloch, lovely paintings by Nancy Hagin and entertaining stories. Anthropologists have insights about Papua New Guinea and Burma to share, while storytellers have a couple of stories about places you might be going to yourself: http://www.persimmontree.org

RECENT BOOKS FROM HAMILTON STONE EDITIONS AND IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, BOOKS RECEIVED, CONTESTS, WORKSHOPS, READINGS ETC.

Through the Riptide: Colin Preston Book Two by Bert Murray and Phyllis Fahrie: An attractive thirty year old professional woman leaves NYC after being attacked there and finds a new job by the seashore. She has to decide whether she will date her ex-boyfriend or a mysterious new man she meets on a bus ride. Filled with passion, emotion, romance and the excitement of a summer by the sea...

New Publisher/Editor for Möbius Gail Taylor is the new Publisher and Editor-in-Chief ofMöbius, The Poetry Magazine. The magazine has a 32-year history of publishing poems by influential artists including four United States Poets Laureate (Billy Collins, Rita Dove, Charles Simic, and Natasha Trethewey). Taylor says, "I am super excited to lead Möbius, The Poetry Magazine. [It] has thrived under the leadership of [Juanita] Torrence-Thompson and Ms. Hull Herman. The magazine got started in the Midwest before it became headquartered in New York. Now, with this transition, a new editorial team gets a chance to carry on the tradition while being open to the possibilities of new aesthetics that reflect themes of resilience, migration, and geography. Aesthetically, this change of course presents new creative possibilities."

Galal Chater in Thuglit Galal Chater has a short story in the literary crime fiction magazine Thuglit. There is a paperback edition and a Kindle edition.

Just Published: Death: A Novel by Fred Skolnik In this multilayered novel, Fred Skolnik creates an intriguing narrative that begins and ends with a burst of red light in the sky. Who is the narrator and what is the meaning of his journey? Ostensibly set in a Hollywood milieu and containing elements of the thriller, Death unfolds in a dreamlike atmosphere where ancient and modern mythologies are woven together as the unnamed hero seeks to evade his pursuers and escape his destiny. It is a novel that will remain with the reader long after he turns the last page. Available at Amazon or through the publisher Spuytenduyvil.

Peter Speziale Story noted at New Millennium Writings!

Peter Speziale has won Honorable Mention for "The Magic Butterfly" in the 39th New Millennium Writings Short-Short Fiction Contest. Look for the list at

www.newmillenniumwritings.com.

Debut Novel from Matthew Neill Null

Matthew Neill Null's debut novel is Honey from the Lion, to be published by Lookout Books on September 8th, 2015. The publisher says, "In this lyrical and suspenseful debut novel, a turn-of-the-century logging company decimates ten thousand acres of virgin forest in the West Virginia Alleghenies—and transforms a brotherhood of timber wolves into revolutionaries....[The novel] evokes the ecological devastation and human tragedy behind the Gilded Age, and sings both the land and ordinary lives in all their extraordinary resilience."

Eric Fritzius Short Stories Now Available

the same sit-at-the-computer energy as writing and putting out newsletters.

So it's been a while since I did #177. However, lucky for me and those of you looking for books to read--Ihave a lot of help with reviews. This issue includes a review by the indomitable "Almost Heaven White Water Rafting Outfitters and Book Club" of a novel by the late William Demby set in the city in West Virginia where I was born; a review of Cat Pleska's memoir by Phyllis Wilson Moore; and a hilarious, enthusiastic response to Mitch Levenberg's Write Something written by Deborah Clearman.

There's a lot more--short reviews and longer. If there's no byline, I wrote it.Also, be sure and take a look at the new contemporary Appalachian story collection from Bottom Dog Press, Appalachia Now.merit; but she wondered if her second reading was influenced by the book’s reputation. She posed the question to our club—“Is Beetlecreek a classic?”

I think it’s fair to say we answered yes. This review summarizes our reasons. The quotes are verbatim opinions of some of the members.Published in 1950, Beetlecreek has been in print for over half a century. While it doesn’t yet have a strong claim on being a “classic” as a work that has stood up over time, it has a good start in that direction. In representing this microcosm with profound authenticity, it represents a “class” or group of a certain place and time—in this case, people living in the Black community of Glenn Elk, near Clarksburg, West Virginia, in the 1940s. At the same time, it powerfully addresses universal issues.Beetlecreek “examines the contradictory needs of human beings to belong to a social group and to escape from the constraints of society. Demby applies the theme in a unique way to the black experience and in a particular to blacks isolated in a small community.” The novel is “about alienation of identities and the use of the African American experience as a metaphor for all lives denied dignity in American culture or society in general.”It’s clear from the first few sentences that this novel is going to be way out of the ordinary. It is a unique coming-of-age story about a Black teenage boy, his uncle, and an old White man. Its depth and honesty in facing the ugliness of reality (and maybe not even seeing it as ugly, but just human) are perhaps the most original things about the book and part of what make it a classic.Bill Trapp is “the mover of the action.” The only White character who is central to the story, he is an outcast of both the White and Black communities. Trapp has lived as a hermit for years; and in the opening scene, he starts to chase away some Black boys who are stealing apples from his apple tree. One of the boys, Johnny, doesn’t run, and Trapp ends up inviting him to sit down on the porch and have some cider. Not long afterward, Johnny’s uncle David comes by to get his nephew, and the three sit and talk a while longer. With this scene Demby introduces the story’s three main characters, all of whose lives are changed dramatically by the events that come out of their meeting.An alternative title under which the novel was published at least once is Act of Outrage. And there are outrages of many kinds and at many levels in the story. One of the most obvious is the outrage of racism. Johnny’s uncle, David, says that for him, ‘Negro life was a fishnet, a mosquito net, lace, wrapped round and round, each little thread a pain.’ ” In fact, the back stories of all three protagonists are characterized by the entrapment of poverty and abandonment; but the major outrage in terms of the plot is an imaginary outrage that engenders a real one.Encouraged by the friendly manner of Johnny and David, Trapp’s conviction to change his life and become part of a community grows. He decides to have a picnic for the local children, both Black and White. Though there appears to be nothing salacious in Trapp’s party plans, an undercurrent of sexuality runs through the story; beginning to end. Demby doesn’t lead the reader much, however, and sexuality as related to children surfaces overtly only in the shack that serves as a clubhouse for a group of teenage boys who live in Beetlecreek. In the privacy of their shack, they look at pornographic pictures and masturbate. Though Johnny is reluctant to join in, his sexuality is part of the story, too.One of the girls at the party, a girl named “Pokey,” finds a picture of a naked person, tears it out of the book, takes it home, and gets caught with it. The page is from an anatomy book, but she and the adults who see the picture consider Trapp to be a pedophile. In the face of the community’s indignation over Trapp’s supposed imposition on young girls, Johnny and David give in to popular opinion even though they think this opinion is wrong.The story ends in violence and even greater betrayal, as well as questions about the destiny of all three main characters. Demby’s novel is engaging in its humanity and depth and, maybe most of all in the questions it raises—calling to mind another definition of a literary classic: “a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.”what she heard and saw, but like a camera obscura, she recorded it to ponder.

In RIDING ON COMETS we meet a loving, imperfect, intelligent, working class family. The men drink and smoke too much but hold on to their repetitive jobs. They carouse, hunt, and fight with each other while the women bond and worry about the men and each other. Depression rears its ugly head.Money is scarce but love isn't.Little did they know the child in their midst would preserve their lives and share them with the world in a truthful, sometimes humorous way. She recalls their superstitions, folk sayings, and quirky habits. One of the most humorous incidents related in the memoir is told first by the grandfather, then by the father, and finally by the daughter. Each voice is unique and each version has its own flair.There are poignant chapters about the mundane realities of death: the necessity of buying new underwear for your father or choosing a wig for your mother. Pleska writes about the fears as well as the joys of childhood, about her father's life long curiosity and her mother's love of books. Thankfully, all the monsters under her bed proved imaginary and harmless and she survived to record this legacy of love.up the art world in disgust and start a second career in an equally farfetched endeavor and write a novel that wouldn't be funny and dark like a Mitch Levenberg story but rather just another divorce story. And even my divorce wouldn't have half the existential angst I see in every Mitch Levenberg paragraph. Maybe you have to be Jewish to have angst?

I would never write a sentence as perfect as "he too snores who only sits and waits."Just a few minutes ago while reading Mitch Levenberg I was struck by the irresistible urge to write about Mitch Levenberg, but first I had to extricate my laptop from under the tray table in the middle seat of a cross-country Jet Blue flight. Perched on the tray table next to my Kindle was of course a cup of hot coffee. Who can read Mitch Levenberg without being filled with a craving for hot coffee? Nearly every other essay in WRITE SOMETHING extolls the power of coffee to raise us to the heights of creativity. In the words of Mitch Levenberg, "I always think coffee. First I think, 'Am I still breathing?' and then I think coffee. Not always in that order." Or how about, "Does it bother me that coffee beans could be extinct by 2080?. . .just the juxtaposition of the words coffee and extinct sends chills down my spine and lethargy spreading throughout my nervous system." Furthermore, "Those two extra cups of coffee every morning provide me with the absolute certainty that I can accomplish anything. . .provide me with the desire to love the world and figure out how to save it all in one streaming heart. .. . "As I lifted the tray table a mere fraction of an inch and wrestled my laptop out from under my feet, naturally I spilled hot coffee on my lap. This excited the passenger beside me at the window seat, a woman my age who was doubtless familiar with rescuing beverages left in precarious positions by children and grandchildren, and she instinctively swooped in to grab my coffee. Thus further humiliating me after an earlier humiliation when trying to lift my excessively heavy carry-on bag into the overhead bin, I resisted help from a kindly gentleman in the row in front of me and chose instead an elaborate acrobatic feat of climbing onto the armrest of a seat not even my own. When I was still unable to raise my carry-on I finally acquiesced to the offer of help. My embarrassment was increased when I was sure I overheard the passengers in the row in front of me discussing the fact that I had nabbed a spot in the overhead bin that was in fact not my spot. It was a row ahead of my spot. This I had done in an effort to stow my bag in front rather than behind my seat, so that I wouldn't have to wait for the entire plane to unload before retrieving my bag. I was fairly certain they had taken note of this aggressive, or should I say passive/aggressive, move on my part.And now I will spend the next ten days with coffee stains on my brand new khaki pants.So I move on to Mitch Levenberg's story "Redemption" because I am feeling in need of some redemption myself and I'm hoping to pick up some wisdom beyond just the wonderful effects of hot coffee. I'm struck by the other half of WRITE SOMETHING, which is not only about writing but is also about the unique writerly experience (Here I must digress. When I was in art school there was a lot of discussion about the word painterly, which we used rather a lot in critiques. What do you mean, painterly, some combative fellow student would ask, probably a sculptor—the sculptors were all conceptual artists at the time. How can you make painter into an adjective? Is there a word sculptorly? Hah! I offer my ripost forty years later in writerly.) the unique writerly experience of reading one's work out loud in front of an audience.I am struck by Mitch Levenberg's relationship with the act of reading—a love/hate relationship of course—and how it affects his relationships with his stories. How his stories become characters as he presents them to an audience. While I think of my stories as my children—to be nurtured and supported and sent out into the world to stand on their own two feet—Mitch Levenberg thinks of his stories as lovers. He must prove himself worthy of them over and over, and only then will they reward him by delighting and seducing his audience, only then will they redeem him.Could I redeem myself in the eyes of the woman in the window seat (who has been working on some kind of legal document on her laptop while I discreetly peer over her shoulder trying to figure out what program she's using) by reading her this review of WRITE SOMETHING by Mitch Levenberg?Or would she find me out as the imposter I am. Now that I have written my own version of a Mitch Levenberg story, I suggest you read the real thing. They're much better.us deep into a time and place– and the lives of ordinary people. Part of what makes the book successful is the narrowness of this slice of reality: Keith painstakingly and with great artistic talent draws the various types of aircraft involved in the bombing and defense of London. He experiences almost nightly interruptions of sleep to go to the bomb shelter.

Otherwise, his life and the lives of his friends are made of family, play, and conflict just like any child's. He has a proud worker father and a middle class-aspirational mother, along with a new baby brother. Life on his street is full of urban games and neighbor kids and a lot of colorful aunts and uncles.I would have been satisfied to spend the novel in London with these people, hurrying down to the shelters when the air raid sirens go off, going back to bed when the all clear is rung. There's a real beauty to the way the British defiantly continued their lives, the children hardly understanding at all why it was all happening, even a bright, imaginative boy like Keith.Keith is, however, sent to the countryside for his safety, where he lives with two Americans in a troubled marriage. The male American, Robert, and the third adult in the household, Norman, are professors much given to discussions about sociology and psychology. They focus their attention on the psyche of poor Keith, whose father is perhaps distant and cool, but hardly anything out of the ordinary.In the end, all the brainy speculations of the adults collapses into the reality of life: Robert begins an affair with one of his students, the brilliant and beautiful daughter of an African diplomat, and Keith, in a misguided burst of racism and a desire to protect his adult friends, attacks her. Meanwhile, the bombs fall in the rural areas, too, and in the end, everyone returns to London– as if that great city were for all of them, not only for Keith, the heart of human struggle.Keefie is available from the publisher at http://www.pennilesspress.co.uk/books/keefie.htm .benevolent dictator of the small world of this story. Naturally generous, she yet believes that blood and class are fundamental to social order.

The reader's first inkling that her benevolence is associated with some real bad stuff is when she goes off on a rant about how the lower orders should never be educated. Then, as evidence, Lady Ludlow relates a long story-within-the story about the French Reign of Terror and a young aristocrat who escapes to England and is under the protection of her and her husband. He then goes back to France to rescue the cousin he loves, and they are both guillotined. To Lady Ludlow, this tragic romance is supposed to prove how wrong it was for her agent to teach the bright young son of the local poacher to read and write!The whole book is told with Gaskell's light touch (like Cranfordbut not her "industrial" novels). Bit by bit, Lady Ludlow's old ways are shown up: the young vicar who wants to start a school finally does start one; the poacher's son he taught to read turns out to be a success; an illegitimate girl (Lady Ludlow has always ignored the existence of anyone born out of wedlock) comes to live with one of Lady Ludlow's good friends. And gradually, Lady Ludlow makes her peace with these changes.Near the end, there is a scene where she entertains for tea a number of people she has pretended didn't exist through much of the story. One ignorant nouveau riche woman with a showy new dress spreads a bandana on her lap to protect her dress from spills. The other ladies titter, and Lady Ludlow proves that truly good breeding is ultimately about kindness: she pulls out her own handkerchief and puts it on her own lap in solidarity with her guest.I especially like Gaskell's insistence that people can change. Lady Ludlow has been a good-hearted person in many ways from the beginning. She is also a woman who, we learn almost in passing, has lost almost her entire family: all nine of her children die before her. That, I remember was one of my strongest reactions to reading Cranford: how all the silliness and pettiness and small mindedness and comedy is set against a background of constant death from illness and accident.Angels of the Appalachians by Deanna Edens

This is a short e-book-only of linked stories about two women from southern West Virginia, Ida and Erma. There is also a more contemporary figure, Annie, who is a student in the 1980's and a married woman in the present, who talks to the older women and learns their histories and shares some of their final years.The big city Ida and Erma go to is Charleston WV, the state capital, where they work their way through college. The small town they come from is Thurmond in the New River valley, a coal and railroad town in its heyday in the early twentieth century.The background to these stories is a time when men died in the mines with brutal regularity, and the United Mineworkers was just organizing. The kindly Mrs. Jones who helps out the girls' families is a relative of Mary "Mother" Jones, the union organizer and firebrand. The lives of Ida and Erma, as filtered by the much younger Annie, are told with humor and a light touch, emphasizing the happy moments and real life angels of the region.Books for Readers Newsletter by Meredith Sue Willis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.meredithsuewillis.com. Some individual contributors may have other licenses.

No comments:

Post a Comment