Books for Readers # 149

February 1, 2012

It looks better online! Read it here.

In this Issue:

Free e-mail subscription to this newsletter.

To create a link to this newsletter, use this permanent link .

For Back Issues, click here.

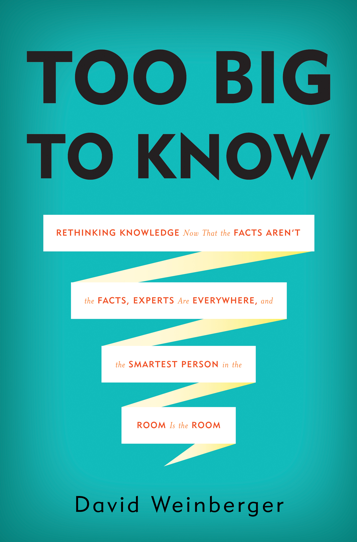

I don't generally send out a new issue quite so quickly, but I'm excited about the new book by my brother-in-law, David Weinberger, Too Big to Know. Weinberger is a Senior Researcher at Harvard University's Berkman Center for the Internet & Society and author of (among many other things) Everything Is Miscellaneous, and The Cluetrain Manifesto (with others). He is a big picture thinker about issues of the Internet, digitalization of knowledge, and much more. He holds a Ph.D. in philosophy (he specialized in Heidegger) and has written comic strip scripts for Woody Allen. He and I once tried to write a novel together, a rousing failure, but I did get a name from it for a minor character in my Marco books for kids.

As you can see, I'm talking about this book personally. There are plenty of reviews and blogs about it from experts in the field, so google it if you're interested.

I have pretty much taken my entire understanding of the Internet/digital age from David's books and conversation. He has give me hints or instruction in everything from choosing a program for making my own website to the idea of the Internet as non-hierarchical and better for conversational than fine writing. I've now advanced far enough on my own to disagree with him occasionally– some of the finest new poetry, for example, is being published in online journals. It is true, though, that the Web world is ideal for getting ideas up and out, and for sharing and discussion and elaborating. It is this communal or at least collective wisdom that is one of Weinberger's primary themes in Too Big to Know. A small example: I have a page of resources for writers on my website, anda few days ago I received a testy but accurate e-mail from a total stranger informing me that one of my links was not just broken, but that the person I had linked to was dead. I deleted that link and fixed a few others while I was at it. The help, if not the kindness, of strangers.

Too Big to Know is full of much richer (a favorite Weinberger compliment) examples of people working together with strangers in group creativity, which he sees as the opposite of "roup think." Wikipedia is the obvious example that we probably all recognize, but in his chapter on networked leadership styles, Weinberger writes about how, after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the street names of Port-au-Prince were named on maps for the first time. An organization called OpenStreetMap.org had satellite maps, but lacked street names in Port-au-Prince, which were sorely needed during the crisis. People from all over the world, mostly Haitians abroad, contributed the names so that the map filled up and aided in the work of everyone from the US Marines to the World Bank and the UN.

Weinberger also has a long and excellent chapter on the changes in science due to the digital era and the Internet. He compares Charles Darwin's years of painstakingly taking barnacles apart to the new way of doing science that has scientists posting on the web vast amounts of raw data as well as unfinished theses for critique and suggestions. One interesting change is that scientific results in the past rarely considered publishable in print-- negative results -- are now not only available but proving to be highly useful. Books and paper journals were simply too expensive to publish what appeared to be dead ends. Yet, negative results of experiments, tentative results, gigabytes of raw data-- all are now increasingly available to the scientific community, enabling discoveries and insights that would never have happened the old way.

Weinberger acknowledges the doomsayers who think we are getting lazy from the Internet ("Let Me Google That For You" ), and worse. He says,"The Internet has broadened science and increased its reach. There are few scientists who would undo the Internet....At the same time, it seems incontestable that this is simultaneously a great time to be stupid. If you want to ignore the inconvenient truth of science, you can surround yourself with a web of ignoramuses who...make falsehoods seem as profound as truths." (Too Big to Know, New York: Basic Books, 2011, p. 156.) If you are unfamiliar with the phrase "echo chamber," this book explains it– how it is easy to find vast amounts of real estate on the web where we only learn from, listen to, and converse with those with whom we agree.

Another especially interesting theme running through Too Big to Know is how the physical limits of a hard copy book and the economics of publishing have shaped Western thinking for centuries. And now we have before us the open and fluid possibilities of digital publishing, e-books, and the Internet. One final goody in the book: Weinberger offers an easy guide to Postmodernism starting on page 88. For me, being able to have an outline of Postmodernism is worth at least $26 dollars.

Even if this is not the kind of book you usually read,you should at least flip through the pages: it is well-written and witty. Don't miss the final chapter on "Building the New Infrastructure of Knowledge."

A Storm in Literary Waters

If you've missed it-- and I did until recently-- there has been a literary donnybrook over Harvard critic and scholar Helen Vendler's review in the New York Review of Books of The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry edited by former US Poet Laureate and Pulitzer prize winner Rita Dove. Vendler denigrates Dove's choices and writing style; Dove responds accusing Vendler of closed minded adherence to the white male canon, and the blogs and magazines are off to the races. For a summary of the positions, take a look at the article in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

I tend to be of the inclusive party rather than the exclusive one, but I was particularly struck by Dove's comment that some of the missing poems and poets (Allen Ginzberg, Sylvia Plath, the later work of Wallace Stevens and more) were simply too expensive to get the rights for. Was Penguin too cheap? Probably, but the underlying problem is how our copyright laws are being used for big profit for big business (See my review of James Boyle's the Public Domain: Closing the Creative Commons of the Mind)..

The good news is perhaps some expanded interest in poetry beause of the controversy?

Two More Books...

I ready my first Stephen King novel, The Shining, thanks to Kindle and the South Orange Public Library. I was not surprised that the story had lots of momentum, and I really liked how skillfully King slips the Evil Force into his characters' minds, and how the characters move in and out of sanity, possession, dreams, visions– impressively well modulated. It was plenty scary, but my narrative intuition told me the kid was going to live and probably the mother. My sense of this was based mostly on where chapters ended– a lot of close calls that

seemed to indicate the endangered one was going to be back. The big narrative question for me was, which father figure was going to die?

I admired the telling of this a lot, but for me, there is still a basic problem with horror, which is: yeah, but why? I don't feel this about good science fiction or carefully built fantasy– I think it's because those worlds, however alien, have stable rules. In them, there is terror for a reason– because there's a war, or because some person wants revenge, etc.– it's part of the whole. And I suppose you could make a case that this novel is a massive exaggeration of how an alcoholic damages his family, except, I don't think psychological insight is the point. In fact, a lot of it seems to be simply about what they

used to call in nineteenth century fiction effects-- the creation of certain sensations. And this makes me feel manipulated in spite of admiring the narrative technique.

I also read the highly popular literary novel The Tiger's Wife by Téa Obreht. A lovely book in so many ways, and I especially liked the Balkan background, but the Grandfather's tales run away with the show, as perhaps they're supposed to.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, NEWS, CONTESTS, WORKSHOPS, READINGS ETC.

Miles Klee's debut novel IVYLAND is just out from OR Press. Take a look at http://www.orbooks.com/catalog/ivyland/ . To read what the NEW YORK OBSERVER says of the book, see http://www.observer.com/2011/08/awl-pal-miles-klee-sells-novel/ .

Julia Kaminsky has a new story up at .decompmagazine.com .

Check out the Vermont Poetry Newsletter for events and more in Vermont.

Cheryl Denise has a new poetry CD. Preview it at www.cdbaby.com/cd/cheryldenise . She reads 13 of her own poems, and a musician friend plays some mandolin and guitar music in between. The poems are from her two collection, I SAW GOD DANCING and her upcoming February 2012 WHAT'S IN THE BLOOD, by Cascadia Publishing House.

Lots of good reviews for Leora Skolkin-Smith's new novel Hystera such as this one: "Leora Skolkin-Smith's new novel... provides a very vivid sense of being in the head of someone having a psychotic breakdown, and is a powerfully useful reference book for dealing with the mental-health system. It also pungently evokes the gritty New York of the '70s."

—Robert Whitcomb, reviewer "The Providence Journal;" excerpts featured recently at http://readysteadybook.com; and an interview at WBAI: http://www.catradiocafe.

No comments:

Post a Comment