(photo by Dory Adams)

(photo by Dory Adams)Monday, October 18, 2010

The Tenth Annual West Virginia Book Festival

(photo by Dory Adams)

(photo by Dory Adams)Saturday, October 09, 2010

Parakeet and Pepper

Here's what I do when things get slow at home: I photograph Taxicab the parakeet making friends with a Carmen pepper just plucked from the fall garden. He's especially talented at grabbing objects with his left foot and moving them to what he considers a better location.

Here's what I do when things get slow at home: I photograph Taxicab the parakeet making friends with a Carmen pepper just plucked from the fall garden. He's especially talented at grabbing objects with his left foot and moving them to what he considers a better location.

Wednesday, October 06, 2010

Books for Readers # 135

Note: Books for Readers # 134 is here.

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers #135

October 3, 2010

MSW Home

For a free e-mail subscription to this newsletter, click here .

Note: If you want to link to something in

this newsletter, use the permanent link here .

The Hamilton Stone Review # 22

Is Open for Poetry and Nonfiction Submissions.

Featured This Issue:

Carole Rosenthal on Franzen's New FREEDOM

A Memoir About the Hutterites Reviewed by Wanchee Wang

Jeffrey Sokolow on History and Post Soviet Documents

News

Tooting My Own Horn:

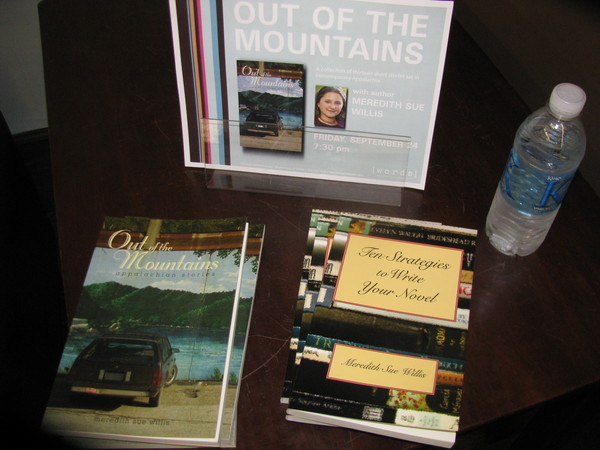

Two New Books:

Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel--Sample here--

and Out of the Mountains-- short stories-- Sample here)

This issue has a nice variety of reviews: Carole Rosenthal talks about that brand new hot literary property, Jonathan Franzen's FREEDOM, which she generally likes, but wonders if our Appalachian (and other) readers think it condescends to West Virginians. Jeffrey Sokolow writes about more espionage literature, with a focus on the American Communist Party, and Wanchee Wang reviews a memoir of a woman who grew up as a Hutterite.

I'm going to be brief and say a word about STRUCTURE AND SURPRISE:  ENGAGING POETRY TURNS edited by Michael Theune, about reading poetry. STRUCTURE AND SURPRISE introduced me to a number of poets I had never heard of, and also suggested a raft of new ideas for writing exercises. The idea of the book is that an important approach to poetry is to focus on structures that produce the turns that are (these writers believe) essential to poetry: everything from “concessional” poems of the type of Shakespeare’s sonnet “My lady’s eyes are nothing like the sun” (but I love her anyhow!) to “emblem” poems that describe at length then meditate on the object of description, like Elizabeth Bishop’s superb “The Fish.” The most fun for me, aside from meeting new poems and poets, was being guided. I’m not a very patient reader of poetry, so this was a pleasure. The only part of the book that didn’t delight me totally was the long final chapter where various poets analyze their own work: it seemed to me too much the result of MFA classes, as if these poets had all been waiting for this moment– to explain their own genius to the world.

ENGAGING POETRY TURNS edited by Michael Theune, about reading poetry. STRUCTURE AND SURPRISE introduced me to a number of poets I had never heard of, and also suggested a raft of new ideas for writing exercises. The idea of the book is that an important approach to poetry is to focus on structures that produce the turns that are (these writers believe) essential to poetry: everything from “concessional” poems of the type of Shakespeare’s sonnet “My lady’s eyes are nothing like the sun” (but I love her anyhow!) to “emblem” poems that describe at length then meditate on the object of description, like Elizabeth Bishop’s superb “The Fish.” The most fun for me, aside from meeting new poems and poets, was being guided. I’m not a very patient reader of poetry, so this was a pleasure. The only part of the book that didn’t delight me totally was the long final chapter where various poets analyze their own work: it seemed to me too much the result of MFA classes, as if these poets had all been waiting for this moment– to explain their own genius to the world.

STRUCTURE AND SURPRISE now takes a place in a group of books that have helped me throughout my life in my relationship with poetry. My first one was the inestimable John Ciardi’s HOW DOES A POEM MEAN? published in 1959, and read by me in my final year in high school, at a time when I was terrified and thrilled with college coming. Ciardi’s emphasis on “how,” which was not how I had approached any literature before, was a mind blower. Also important to me (and aa much shorter book, I notice, as befits a twentieth-century work) was Camille Paglia’s BREAD, BLOW, BURN: CAMILLE PAGLIA READS FORTY-THREE OF THE WORLD’S BEST POEMS. This came out in 2005, and it gives a full chapter to each poem. Most are short (lots of sonnets) including Shakespeare, Donne, Wordsworth, then Jean Toomer, Roethke, and some people I’d never heard of.

I recommend all three of these books highly for an informal approach to poetry.

Carole Rosenthal on Jonathan Franzen's FREEDOM

I just finished Jonanthan Franzen’s FREEDOM last month and really enjoyed it despite the ubiquitous hype for this novel--which both whetted my interest and made me wary. Now a critical backlash has set in, and I seem to be one of the few readers among my friends who admire the novel.

Franzen IS a terrific writer, an easy stylist whose voice is supple and engrossing. Beginning with comic book-like brightness and intensity, FREEDOM gradually unfolds as an epic tale of the all-American Berglund family--Walter, the father, a liberal do-gooder of the pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps variety; Patty, the needy mother, a glib ironist who pushes away family intimacy; Jessica, the sensible daughter; and Joey, the rebellious son who becomes a right-wing entrepreneur. Chronologically FREEDOM begins and ends in Minnesota, spanning the Nixon years to the present. The novel travels the American landscape and explores our shifty and shifting politics, economic changes, and national aspirations over time. The Berglunds endure many personal travails and Franzen's vision is darkly comic, almost satiric, yet he is also tender towards the Berglund famly. In fact, the book struck me as arguably sentimental in its wry, redemptive wrap-up, reminiscent of certain 19th century epic novels.

The ethics and psychology of the Beglund family members is counterpointed by  Walter's long-time friend and former college roommate, Richard Katz, a punk rock star of the Lou Reed ilk, whose creative passion, integrity, and personal indifference eventually wreaks havoc on the family--a healing havoc. The fragmentation and eventual individuation of the Berglund family is the central story here.

Walter's long-time friend and former college roommate, Richard Katz, a punk rock star of the Lou Reed ilk, whose creative passion, integrity, and personal indifference eventually wreaks havoc on the family--a healing havoc. The fragmentation and eventual individuation of the Berglund family is the central story here.

The Berglunds' experiences are intended to represent American experience, and this ambitious vision of Franzen's poses its own problems. For instance, no people of color are represented in the novel, with the single exception of Walter's love interest, a beautiful South-Asian American organizer whose interiority is insuffciently probed; also, she conveniently disappears. The Berglunds themselves, Minnesotans, are white and upper middle-class.

Yet a pivotal section of FREEDOM is set in West Virginia, and involves heinous mountain-top removal for mining coal. Walter, an idealist, hooks up with a Halliburton-like company whose overt intention is to create transglobal bird refuges and new jobs for the unemployed and working class who must be relocated, although this is obviously a cover story. Walter's secret plan--never entirely clear--is to begin to save the world from overpopulation with this leveling of the mountain. Walter is naive and also condescending to the West Virginians he encounters--indeed, to the working class in general. When his personal agenda is thwarted, Walter's rage overflows.

Yet I couldn't help wondering how West Virginians respond to this quick-study portrait of their state. Although the condescension is expressed from Walter's point of view, the author himself--certainly not naive--seems to be complicit in this view. (Walter, like Franzen, is an avid birdwatcher, and Walter's love of birds and nature is central to his later actions Franzen, on the other hand, seems to be employing the technique of limited direct third person to cover his tracks.)

I won’t bother to further recount the characters or plot, since Franzen and FREEDOM have been so widely discussed and publicized, but I would be interested in what others think.

WANCHEE WANG REVIEWS I AM HUTTERITE BY MARY-ANN KIRKBY

“Mommy, are you a Hutterite?”

For years Mary-Ann Kirkby hid her Hutterite background, even from her young son. His innocent question prompted her to write this gentle memoir about her Hutterite childhood. In so doing, we get a peek into a little known community of faith.

Like their Amish and Mennonite brethren, Hutterites trace their beginnings to the religious turbulence of 16th century Europe. Founded by Jacob Hutter in 1528, Hutterites organize their communities based on the principles of communal property and life as found in Acts 2: 44-45: “And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; and sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.” You could say that the Hutterites practiced an early form of socialism, even while pre-dating Marx by three centuries. Fleeing persecution, they came here in the 19th century. Today there are 45,000 Hutterites living in North America, mostly in the prairies of western Canada and northwestern United States.

The first part of the book describes her parents, their courtship and marriage, and sets up the background for their family’s eventual departure from the colony. It also introduces us to the rhythms of Hutterite life where “women did the cooking, baking, and gardening while the men carried out the farming, mechanical, and carpentry chores.” At age two, she entered Kleineschul or kindergarten, learning German songs, stories, prayers, and games. By her account, it was a happy childhood. “As children, we found contentment in the bosom of colony life and in the routines that directed every new season.”

With limited contact with the outside world, colony life was simple, filled with hard work and dedication to community. “Regardless of age or capacity, each member had a station to fill and meaningful work to do. No one received a salary, but everyone’s needs were met. Sharing a common faith, most colony members were satisfied with a sustainable lifestyle that nurtured them physically and spiritually from cradle to the grave.”

But even communities of faith are not free from internal conflicts. Years of disagreements between her father and the colony leader caused her father to make the draconian decision to leave when she was ten. Her family was thrust headlong into a modern society that sneered at their ways. The upheaval was predictably painful and wrenching. “In school, we collided head-on with popular culture…We didn’t know how to swim or skate or ride a bicycle. We had never tasted pizza, macaroni and cheese, or a banana split - rites of passage in mainstream society.”

Despite all this, Ms. Kirkby never veers into self-pity or bitterness in describing their difficulties. Parts of the book could have used some judicious editing to pick up the slow pace (but then again, I’m from a fast-paced society). In writing this book, she finally comes to terms with her past and imparts the richness of the Hutterite culture to her son. We are also richer for these glimpses into the Hutterite world.

Jeffrey Sokolow:

Some time ago, I wrote about my interest in espionage literature, especially biographies of and memoirs by participants in such work (link to: http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/bfrarchive111-115.html). The vast trove of documents spirited out of post-Soviet Russia by the most unlikely of dissidents, the long-time KGB archivist Vassily Mitrokhin, also is well worth reading. Two volumes of files have appeared: The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB and The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the the Third World: Newly Revealed Secrets from the Mitrokhin Archive (both with the British historian Christopher Andrew. In these documents, workers at the Soviet Center speak directly and in as unfiltered a voice as we are likely to get now that the "ex"-KGB apparatchik Putin keeps a tight lid on the archives.

One fruitful topic for study on which a large and growing literature exists concerns the espionage activities of American Communist Party members. Although it would be false to say that most American Communists were spies, in the Stalinist era, before disillusion with the romance of Communism set in, the great majority of Americans who assisted the Soviet secret services were members of the Communist Party. Of course, most American Communists were blissfully unaware of the party's secret apparatus and were involved in trade union, civil rights, or other purely legal activities. But the party, like all Comintern member parties, had a clandestine capability that provided a natural segue from affording an ability to function underground during times of repression to conducting clandestine activities in normal times, including carrying out espionage work for the worker's true motherland. To the Soviet Center, CPUSA members were known as "fellowcountrymen." Many of them came from families that had fled Tsarist Russia, especially Jews, so the term was apt. To the American services, these folks were traitors, but to their colleagues at the Center in Moscow, they were Soviet patriots whatever citizenship they held. One agency's traitor is another's hero.

Two of the most prolific authors in this field are the historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, whose works include Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (with Alexander Vassiliev), Early Cold War Spies: The Espionage Trials that Shaped American Politics, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, In Denial: Historians, Communism, and Espionage, The Secret World of American Communism (with Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov), and The Soviet World of American Communism (with Kyrill M. Anderson).

The improbable story of Elizabeth Bentley, who took over the espionage rings run by her lover, the Soviet agent Jacob Golub, after his untimely death and then betrayed them all to the FBI out of pique when the Center tried to take over her responsibilities in a bid to be more professional and eliminate use of amateurs, is told in two recent biographies: Clever Girl: Elizabeth Bentley, the Spy Who Ushered in the McCarthy Era by Lauren Kessler and Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley by Kathryn S. Olmsted. Another improbable story is that of Judith Coplon, told in The Spy Who Seduced America: Lies and Betrayal in the Heat of the Cold War: The Judith Coplon Story by Marcia Mitchell and Thomas Mitchell.

The Rosenberg case has long been a lodestar for the left, though recently, with the end-of-life confession of Morton Sobel, the left's line has shifted from "they was framed" to "what's so bad about spying anyway?" The autobiographical memoir by Aliexander Feklisov, Julius Rosenberg's Soviet control who later was to play a key role in the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs, paints a very moving portrait of his colleague in clandestine work.

Of course this topic is a hot potato politically: many on the left can't bring themselves to admit the facts (which as Stalin said, are "stubborn things"), while partisans of the right use this long-past history to smear all domestic radicals past, present, and future as traitors and knaves. I recommend that people who just like to read history ignore the political misuse of history on either side and become better acquainted with this fascinating topic and its amazing cast of characters.

THREE SHORT TAKES

Three books I enjoyed last month:

THE FIFTH CHILD by Doris Lessing,  recommended by Alice Robinson-Gilman, a small book, 133 pages, very chilling and realistic. Excellent example of speculative fiction, as Alice said. Only one thing is changed in this world, the one thing being a monstrous child, whose origin is accepted as a given. The novel is about what happens after. It's about the impossibility of creating something perfect, especially a family, especially in real life.

recommended by Alice Robinson-Gilman, a small book, 133 pages, very chilling and realistic. Excellent example of speculative fiction, as Alice said. Only one thing is changed in this world, the one thing being a monstrous child, whose origin is accepted as a given. The novel is about what happens after. It's about the impossibility of creating something perfect, especially a family, especially in real life.

Another very imperfect family appears in a life-and-tmes biography, CATHERINE DE MEDICI: RENAISSANCE QUEEN OF FRANCE by Leonie Frieda This was a solid narrative that pulled together a lot for me about the sixteenth century. And what a time that was. It was the period of the wars of religion in France-- death present and cruel by the hand of enemy religionists. But equally cruel was what happened when people got sick.  Catherine’s three king sons and her king husband die grimly, although she lived to be 69. I was struck by so many things: the public quality of life; the lice and fleas even in royal cloth-of-gold; Catherine's heroic if limited efforts to hold the kingdom together for her sons, to keep her sons alive, and her daughters. The author suggests that she might have been as great as Elizabeth II in England, her contemporary, but that Catherine (who was a native of Italy) lived and schemed for her family whereas Elizabeth's schemes were in the end for England. I liked the book a look.

Catherine’s three king sons and her king husband die grimly, although she lived to be 69. I was struck by so many things: the public quality of life; the lice and fleas even in royal cloth-of-gold; Catherine's heroic if limited efforts to hold the kingdom together for her sons, to keep her sons alive, and her daughters. The author suggests that she might have been as great as Elizabeth II in England, her contemporary, but that Catherine (who was a native of Italy) lived and schemed for her family whereas Elizabeth's schemes were in the end for England. I liked the book a look.

Third, I read and was delighted by William Golding’s The INHERITORS, especially the way he created a way of thinking for his imagined Neanderthal people who live in the moment and think with “pictures.” There is a wonderful emblematic moment when the main character doesn’t get it that the "gift" with a red feather that is suddenly stuck in the tree beside him is dangerous. The "gift" of course is from our ancestors, homo sapiens sapiens, the inheritors. The last part of the book is all about these “new people,” a drunken violent cruel lot, worthy progenitors of the perpetrators of religious wars. This is William Golding most famous for Lord of the Flies.

MORE SUGGESTIONS:

Nancy Haber suggests these from around the world. A TALE OF LOVE AND DARKNESS by Amos Oz; THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS by Kiran Desai; GOD OF SMALL THINGS BY ARUNDHATI ROY; THE BRIEF WONDROUS LIFE OF OSCAR WAO by Junot Diaz. I’m in the middle of the Amos Oz memoir, and really amazed and moved by it:

THE TEACHING COMPANY

I’ve been using the Teaching Company’s tapes and CD’s for trave for many years. They prepare lectures on everything from the philosophy of science to histories of language and of course lots of politics and psychology and literature. Jeff Sokolow recommends Isaiah Gafni's and Lawrence Schiffman's lectures on Judaism and a three part history of the English language by Seth Leher. See the Teaching Company website at http://www.teach12.com/greatcourses.aspx?ai=16281.

New Press

Laura Roble is the CEO of a new publishing company called Heroic Teacher Press. They are a small, independent press with a mission to raise the status of teachers in America . They released their first book earlier this year, LEAVE NO CHILD BEHIND, by first time author R, Overbeck. The book is a thriller about a terrorist takeover of a small high school and one teacher's struggle against the intruders. See www.heroicteacherpress.com

Do You Have Someone Looking at Colleges?

Wanchee Wang has an informative blog about taking her eleventh grader to colleges– what they experiences, what they learned: http://bound4college.wordpress.com/about/ .

West Virginia Encyclopedia is Now Online!

The WV Encyclopedia website shows the state's history, culture and people with pictures, videos and maps and other features about the history of West Virginia. Visit http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/

Announcements and News

Ed Davis has a story “Convergence” appearing in the second volume of the MotesBooks Motif Anthology Series, Come What May, containing short fiction, nonfiction, poetry and song lyrics. Although the 136 contributors are from all over the world, many are southern and Appalachian, reflecting editor (and award-winning writer) Marianne Worthington’s Tennessee roots. In length 323 pages, the handsome book is arranged into intriguing sections such as “Parallel Realities,” “Happenstance” and “Strangers and Kin.” Writers include Larry Smith, director of Ohio’s Bottom Dog Press’, along with recent Antioch Writers Workshop faculty Cathy Smith Bowers and Joyce Dyer, as well as Ed Davis. The book can be ordered for $15 plus postage at www.motesbooks.com.

Writers, note that the editor is collecting material for the next anthology on “Work” with a deadline of November 1, 2010. For details, see: http://motesbooks.com/MOTIF-Call-For-Submissions.html.

Just Out: THE BODHISATTVA’S EMBRACE: Dispatches from Engaged Buddhism's Front Lines by Alan Senauke. See website at http://www.clearviewproject.org/

Barbara Crooker has two new poems up at Verse Wisconsin: http://versewisconsin.org/Issue104/poems104/crooker.html and and at:

http://iambicadmonit.blogspot.com/2010/09/interview-with-barbara-crooker-poet_28.html

Digitalize Your Books!

A good company I've used for turning my hard copy books that were written on typewriters (yes, yes, I know...) into .pdf or .doc files, is Golden Images, LLC at pdfdocument.com. Write to Stan Drew stan@pdfdocument.com, who is very responsive to email, and does the work for what seems like a reasonable price to me.

Friday, October 01, 2010

October 1, 2010

It’s all good, as I wrote to Carole Rosenthal about our coffee and then writers' group last night. We trying to convince Edith to start blogging, and Carol Emshwiller is back from her place in the mountains of California, and Joel called and I'm writing a lot of emails and trying to communicate in my own way.And thinking about this Buddhist concept of No Stable Self, which means me in this place with rain diagonal on the windows, at this moment, and then the rain stops, turns to drops, all twinkles and shades into something else. Why is that concept so helpful to me?

September 28, 2010

Friday night I had such fun with friends coming to hear me read and buy books at Words bookstore in Maplewood, NJ. Below I'm signing for Mira Stillman, herself a wonderful memoirist and Ethical Culture friend. Photo by Ellen Kahaner for Maplewood Patch.

Lots of good news this morning, for individuals, if not for the world:Joel's PHd advisor Dawn Song got a Macarthur grant for heavens' sake!