Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers #131

May 2, 2010

MSW Home

For a free e-mail subscription, click here .

Note: If you want to link to something in

this newsletter, use the permanent link here .

Featured This Issue:

Phyllis Moore on J. McHenry Jones's Hearts of Gold and Kathryn Stockett's The Help

Reamy Jansen's Available Light

Award-Winning Poetry Magazine for Sale

Closing Soon: ONLINE SUMMER SOLSTICE MASTER CLASS takes place on June 21, 2010; June 28, 2010; July 5, 2010; and July 12, 2010. This is a class for writers who are already working on or trying to restart a project of prose narrative like a novel, a memoir, or stories. It is filling up fast, so if you want more information, please see the website at http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/mswclasses.html.

This issue has a guest editor, Phyllis Moore, who writes about two novels on race in America– one a new popular novel, and one that most readers have probably never heard of....

HEARTS OF GOLD AND THE HELP

BY PHYLLIS MOORE

Note from PM: I am indebted to scholar John Sekora, former professor of English at North Carolina Central University, Durham, North Carolina, for his words “black message” in a “white envelope” as a means of describing “as told to” slave stories edited and published by a white person. It is so apt. Because of his example, I consider a “black message” in a “black envelope” one written, edited and published by a black writer.

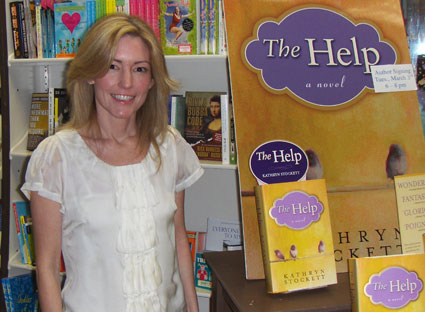

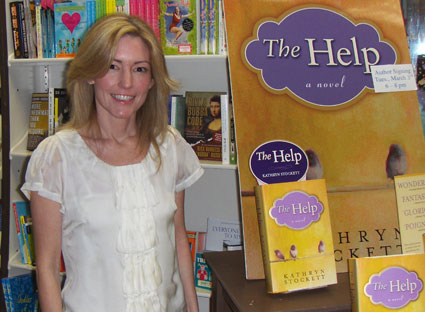

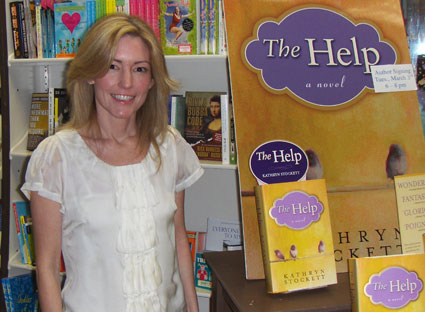

Recently I read two very different pieces of fiction back-to-back, THE HELP (2009) by journalist and author Kathryn Stockett and HEARTS OF GOLD by noted West Virginian scholar, J. McHenry Jones (reprinted in 2010 by West Virginia University Press).

Recently I read two very different pieces of fiction back-to-back, THE HELP (2009) by journalist and author Kathryn Stockett and HEARTS OF GOLD by noted West Virginian scholar, J. McHenry Jones (reprinted in 2010 by West Virginia University Press).

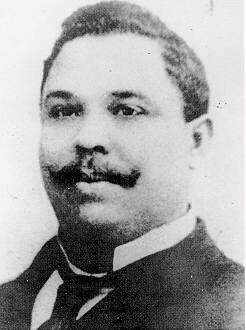

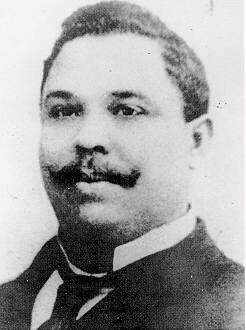

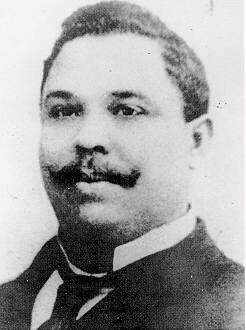

Jones’ work, self-published in 1896 in Wheeling, West Virginia, is what might be deemed a “black message” in a “black envelope.” He was an Afro-American (his term) writing about black life in the North and South during the post-Reconstruction era. This was a daring undertaking for the (then) young principal of a school located below the Mason-Dixon Line. He took a risk when he pointed out, so to speak, the emperor had no clothes and then suggested how to dress him.

Jones, an erudite scholar and savvy, politically-inclined educator, created his cast of characters from the black middle-class, a departure from the slave narratives and biographies common in the day. His characters came in many hues, but all were intelligent, prospering, professional, educated, cultured, Afro-Americans. Fond of quoting Shakespeare and the Bible, they spoke with perfect grammar and diction and had elaborate vocabularies. He was a master of vaulted language and had a point to make.

His characters want to remain in America (no Africa for them) and live the lives of free people. The times are precarious. They recognize the weakening of civil rights laws, unpunished lynchings, proliferation of Jim Crow laws involving voting and transportation, false imprisonment of blacks, slavery-like conditions in the penal coal mine system, sexual harassment, and believe action must be taken. Through education, the church, lodge memberships, and friendships, they learn to use the power of the press to effect changes in the system as well as in public opinion.

What does HEARTS OF GOLD have in common with THE HELP, written by a young Southern white woman more than 100 years later?

THE HELP is set in the 1960s, one of the most brutal decades in our nation’s racial history. It tells the story of black female domestic workers as told to a white writer. It could qualify as a “black message” in a “white envelope.” It was a risky undertaking for a white woman living well below the Mason-Dixon Line. Her cast of characters is not from the middle-class. They are not pursuing professional careers. They are middle-aged domestic workers with the separate-and-not-equal education the South offered. Not protected by laws, they must ride in the back of the bus, drink from separate fountains, use separate toilets and are blocked from registering to vote. Basically, they have no civil rights. Their language is not vaulted; they don’t speak standard English or have perfect diction. By and large, they are decent, honest, hard working, religious, caring people, living the lives Jones’ characters feared would happen if Reconstruction did not live up to its promise.

Jones’ novel is his one published work of fiction and it does show promise. The same is true for Stockett’s. As I read, what struck me was how little changed in the interval between the eras and how glad I am to have both books to remind me.

***

My husband and I are snowbirds. We escape West Virginia’s winters by hanging-out in Gulf Shores, Alabama. When we pull into town, the first three places we stop are the mail box rental, the Winn-Dixie Supermarket, and the user-friendly Thomas B. Norton Public Library. Alabama’s libraries offer all kinds of interesting programs. I especially like the monthly book discussion groups. This year, THE HELP, a novel by Mississippi native and Alabama University graduate (Roll Tide!) Kathryn Stockett was the novel for March.

My husband and I are snowbirds. We escape West Virginia’s winters by hanging-out in Gulf Shores, Alabama. When we pull into town, the first three places we stop are the mail box rental, the Winn-Dixie Supermarket, and the user-friendly Thomas B. Norton Public Library. Alabama’s libraries offer all kinds of interesting programs. I especially like the monthly book discussion groups. This year, THE HELP, a novel by Mississippi native and Alabama University graduate (Roll Tide!) Kathryn Stockett was the novel for March.

Unfortunately for me, all copies were checked out and the waiting list was 30 some persons long. It was the same at every other Baldwin County library. Even more frustrating, local book stores didn’t have a copy either. Clerks said it sold as fast as it came in. They added it was a “must read.” As evidenced by internet comments, it is a controversial novel. Set in Mississippi, it is the story of relationships between young privileged white women and their older and wiser black domestic workers, the help.

The novel is set in the shameful bloody 1960s, a brutal time in the history of this nation. I can still picture the disturbing images: the murder of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King in jail in Birmingham and later leading a march on Washington before being assassinated in Tennessee. For me it was a decade of grief and disbelief: young American freedom riders murdered for trying to assist black Americans to register to vote, blacks unable to enroll in state operated universities, black Americans sitting stoically at Woolworth’s lunch counters while white Americans harassed them. I still shutter at the tragedy of three little girls losing their lives in the bombing of a black church.

Stockett, a baby when most of the events took place, used her imagination to create a novel around an untold peripheral story, the relationship of white boss-women and their black domestic workers. The novel opens in 1960, about the time its protagonist, a recent “Ole Miss” graduate, Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan, returns to her parents’ cotton farm (read plantation) in Jackson, Mississippi. With no real need to work, she lands a very part-time position on the local newspaper. Her plan is to build her resume, move to New York, and write a novel. She has hope; an acerbic New York editor is willing to read some of her work if it is a subject Skeeter is seriously bothered by or passionate about.

Twenty-two-year-old Skeeter is not passionate about anything. She’s rather a dud as a “Southern Belle”– too tall, hair too curly, too studious, too outspoken, not subservient to men, not a clothes-horse. She’s also guilty of speaking to the help (she actually knows the names of her friends’ maids). She is quietly researching Jim Crow laws in various states.

She drifts back into a group of former “Ole Miss” sorority sisters, the ones who chose a wedding ring over a diploma. Like them, she joins the Junior League and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). When not playing bridge or tennis, the clique spends time around the Country Club pool. Of course, Skeeter’s married friends bring along “the help” (read— intelligent black women paid less than minimum wage, women riding in the back of the bus and living from pay check to pay check) as babysitters.

Skeeter’s friends don’t seem to notice the murder of civil-rights activist Medgar Evers, shot in his own yard just a few miles up the road. They are too busy raising money for the poor starving children in Africa (PSCA) and other worthy-to-them projects, such as lobbying for a bill stipulating all newly constructed Mississippi houses include a separate bathroom for the help.

Skeeter begins to question life as she knows it: if the help is too diseased to use the family’s toilet, why are they allowed to toilet train the children and nurse them when they are ill? Why does the help prepare and serve lunch for the bridge club and contribute elaborate desserts for fund-raisers if they are so unclean? Why do they cook for the family and feed the children if they are so germ-laden? How does the help feel about using dishes and silverware set aside for just their use? Why do her friends act as if the maids are deaf to rude remarks?

Skeeter recalls her childhood maid, Constantine, and wonders what stories Constantine could tell about working for Skeeter’s mother. Intrigued, she approaches a friend’s bright maid, Aibileen, and asks to interview her, secretly of course. Skeeter promises to disguise the town as Niceville, not Jackson, and change all the names of the employer as well as Aibileen’s name. Out of fear, Aibileen says no, but when local and national civil rights incidents become more frequent, she changes her mind.

Being able to tell her own story proves cathartic to Aibileen, an avid reader, journal keeper, and would-be-author. She convinces her feisty friend Minny, the most frequently fired maid and the best cook in the state of Mississippi, to be interviewed. Before long, Aibileen and Minny find eleven more women, mostly from their church, who are willing to risk it all by telling their stories.

Over time, the three original collaborators complete the interviews, type and edit them, and mail them to the New York publisher. The publisher likes their unique approach to this hot timely topic and agrees to publish the interviews as a book written by Anonymous.

The understandably nervous collaborators don't expect the book to create much attention. Imagine their reaction when stores can’t keep copies in stock. When a local television personality questions if the maids and the employers in the book just might be from Jackson, every Junior League member rushes out to buy a copy, as does every maid.

Before long, the town’s citizens are irate. If these interviews were done in Jackson, who conducted them? And where? Whose maid said what? Local readers begin a guessing game to match local League members to the goings-on in specific chapters. The most shocking and titillating chapter is about a feisty maid getting even with a nasty untruthful lady-boss. Just who is this lady-boss? Who is the maid?

Stockett obvious took risks in writing this novel. It’s doubtful she will be invited to speak for a luncheon of the Jackson Junior League anytime soon. She also took a risk with language; some readers take issue with the fact her black characters don’t use standard English. That is true, their speech is Ebonics-like. But once readers get a feel for what Stockett is attempting, it might just work for them. It did for me.

Some readers call the language demeaning or irritating, some say it is insulting. To me, the black language is reasonable for middle-aged women raised in an impoverished ghetto-like section of a city in the Deep South. Most of the maids are said to be 40 to 60ish which means they were born between 1900-1920 and went to school around the time of the Great Depression. They had limited educational opportunities and were denied access to libraries.

Stockett is also criticized for imagining what black women felt during this horrific time. Isn’t that what fiction writers do, imagine? She did grow up in the South and I respect her for giving this era her imaginative reflections.

The book has flaws; it is a first novel. Unlike Lake Wobegon, where all the folks, at least the children, are above average, the novel is populated by a lot of nasty folks: social-climbing white women; women who can’t stand their own mothers or their own children; shallow men who drink too much and have questionable values.

The book is also a spectacular success. Dealing with a turbulent time and serious subject matter, Stockett makes events, some tragic beyond belief, more palatable by wrapping them in the events of daily life: babies are born, people go to church, couples fall in and out of love. Her humor helps. She manages to include some laugh-out-loud wacky situations, such as a decrepit naked exhibitionist’s visit to one of the boss-lady’s wooded yards.

Thanks to Stockett, the rights and wrongs of the era are more visible to a new generation in the guise of fiction. The novel is scheduled to become a Dreamworks film and more information is available at http://www.kathrynstockett.com.

Note: for a different viewpoint, look here.

SHORT RECOMMENDATIONS FROM MSW

Let me begin by recommending a small press memoir collection, Reamy Jansen’s Available Light: Recollections and Reflections of a Son. There are a lot of wonderful details of material culture of the  nineteen fifties and early sixties here, and a memorable house that is the center of the family’s lives. The story is full of incident and suffering. But what is most striking about the book is that it manages to treat with delicacy material that would be, in another writer's hands, potentially melodramatic: an alcoholic mother, a distant father, the death of both of them, a threat to the eyesight to the narrator. I don’t mean that Jansen makes light of what is serious, but rather that he handles his stories in the way we are told to handle tender dough– gently, quickly, expertly: with a light touch. Jansen manages, for example, to present his mother’s frantic anti-Semitism in a perfect mix of light and dark, shocking and familiar, near and far, painfully sharp and almost lilting. How does he do that? I think there is an element of grace here-- both grace in its particular Christian usage of freely given and also in our everyday use of the word to mean a kind of effortless charm and beauty. Jansen’s language is graceful, and he offers forgiveness to the deeply flawed people in his past.

nineteen fifties and early sixties here, and a memorable house that is the center of the family’s lives. The story is full of incident and suffering. But what is most striking about the book is that it manages to treat with delicacy material that would be, in another writer's hands, potentially melodramatic: an alcoholic mother, a distant father, the death of both of them, a threat to the eyesight to the narrator. I don’t mean that Jansen makes light of what is serious, but rather that he handles his stories in the way we are told to handle tender dough– gently, quickly, expertly: with a light touch. Jansen manages, for example, to present his mother’s frantic anti-Semitism in a perfect mix of light and dark, shocking and familiar, near and far, painfully sharp and almost lilting. How does he do that? I think there is an element of grace here-- both grace in its particular Christian usage of freely given and also in our everyday use of the word to mean a kind of effortless charm and beauty. Jansen’s language is graceful, and he offers forgiveness to the deeply flawed people in his past.

I also read and admired At Swim,Two Boys by Jamie O'Neill, a lovely book that makes me want to start talking Irish.The history of the 1916 Easter Rising is the background, but the real heart of the novel is the boys’ passion for each other, sexual of course, but also simply for the fullness of life through their love. One of the great triumphs of the book, in an entirely different vein, is the character of Jim’s Dad, Mr. Mack, who is a fool but also a man with a great heart. The novel builds toward a demonstration of the shocking arbitrariness of war. So much is so well done here: the delight and euphoria of patriotism, Doyler Doyle's working class cleverness and confidence. A book deserving of its reputation.

Another book that made me feel I was understanding a foreign language was the highly popular The Yiddish Policeman’s Union by Michael Chabon. I am really fond of novels that do alternative history well, as this one does. Chabon tries out a scenario where the Jews got invited, sort of, to come to Alaska just before World War II. In this version of history, a Yiddish culture develops in Alaska while the Zionists lose the 1948 war in Palestine. In fact, Roosevelt's real life Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes did consider in 1938 offering Alaska as a haven for Jewish refugees from Germany and elsewhere.

After the novel's clever set-up, and once the reader gets used to the beautiful language that translates and (probably) makes up Yiddish syntax and slang (guns are called sholems), it is a Raymond Chandler-esque murder mystery. I lost the plot from time to time, but didn’t care much, as I was mostly in for the good humoredly depressed and drunk and lonely main character Landsman, his huge half native American cousin, and many more. I had the feeling that Chabon didn’t really decide who done it till the very end, but again, I could care less: it is a great ride.

POETRY MAGAZINE AVAILABLE FOR NEW OWNER

Editor-in-Chief/Publisher/Owner of award-winning international non-profit poetry magazine seeks individual or group or college to buy and take over all responsibilities including editorial. Possibility of some reading assistance from current associate editor, etc. for smooth transition. Interested parties contact owner ASAP at: poetrytown@earthlink.net .

READING LISTS ON HEALTH CARE LITERATURE

GOOD STUFF ONLINE

ABE.com books keeps coming up with fun lists: this time it’s Father and son writers:

Barbara Crooker reports a poem from her new book (see her new book below), "Ode to Chocolate," is on the Writer's Almanac for Saturday, April 24th. You can listen here .

Burt Kimmelman has a poem from his new collection AS IF FREE (Talisman House, 2009) that was featuredon The Writer’s Almanac on April 20th. Garrison Keillor read “Taking Dinner to My Mother.”

WriterSites has a lot of good info for writers: http://writersites.blogspot.com/

BEST OF THE WEB

Dzanc Books has published BEST OF THE WEB 2010 guest-edited by Kathy Fish with series editor Matt Bell. This is the newest edition of Dzanc's yearly anthology series compiling the best fiction, poetry, and non-fiction published in the previous year's online literary journals.

BOOK NEWS, CONTESTS, AND MORE

The Children's Book Council has nominated Peter Brown for Illustrator of the Year for his book, THE CURIOUS GARDEN. Congratulations, Peter!

A new picture book HISTORIC PHOTOS OF WEST VIRGINIA by Gerald D. Swick is now available. The volume shows West Virginia's cultural heritage by using lesser known historical photographs in a fresh way. For more information, see http://www.turnerpublishing.com/detail.aspx?ID=1933 .

C&R Press announces the publication of Barbara Crooker's new poetry book, MORE!

Whether writing about her son with autism, her daughter's traumatic brain injury, her mother's slow decline, or paintings by Matisse and Kahlo, Crooker grounds her work in the everyday moment. Divided into four sections with each exploring a different aspect of the word "more," these are poems of grace and gratitude that show "all of us dazzling in the brilliant slanting light." More information at http://www.wix.com/crpress/crpress .

Kal Wagenheim’s 1973 biography of Roberto Clemente will be re-issued in Summer/Fall 2010 by Markus Wiener Publishers of Princeton.

HEART AND CRAFT: A MEMOIR WORKSHOP FOR WOMEN, taught by author/journalist Anndee Hochman, will take place in La Barra de Potosi, Mexico. November 13-19, 2010. For beginning and experienced writers. Early-bird price is $1000 ($500 deposit due by July 1) and includes tuition, accommodations in the magical Casa del Encanto, six days' breakfast and dinner and all taxes/tips. E-mail aehoch@aol.com for details and application.

Open City's 2010 RRofihe Trophy Short Story Contest is now open. Limit: 5,000 words, winner receives: $500, trophy, and publication in Open City magazine. Judge: See the complete guidelines at http://www.opencity.org/rrofihe.html .

nineteen fifties and early sixties here, and a memorable house that is the center of the family’s lives. The story is full of incident and suffering. But what is most striking about the book is that it manages to treat with delicacy material that would be, in another writer's hands, potentially melodramatic: an alcoholic mother, a distant father, the death of both of them, a threat to the eyesight to the narrator. I don’t mean that Jansen makes light of what is serious, but rather that he handles his stories in the way we are told to handle tender dough– gently, quickly, expertly: with a light touch. Jansen manages, for example, to present his mother’s frantic anti-Semitism in a perfect mix of light and dark, shocking and familiar, near and far, painfully sharp and almost lilting. How does he do that? I think there is an element of grace here-- both grace in its particular Christian usage of freely given and also in our everyday use of the word to mean a kind of effortless charm and beauty. Jansen’s language is graceful, and he offers forgiveness to the deeply flawed people in his past.

nineteen fifties and early sixties here, and a memorable house that is the center of the family’s lives. The story is full of incident and suffering. But what is most striking about the book is that it manages to treat with delicacy material that would be, in another writer's hands, potentially melodramatic: an alcoholic mother, a distant father, the death of both of them, a threat to the eyesight to the narrator. I don’t mean that Jansen makes light of what is serious, but rather that he handles his stories in the way we are told to handle tender dough– gently, quickly, expertly: with a light touch. Jansen manages, for example, to present his mother’s frantic anti-Semitism in a perfect mix of light and dark, shocking and familiar, near and far, painfully sharp and almost lilting. How does he do that? I think there is an element of grace here-- both grace in its particular Christian usage of freely given and also in our everyday use of the word to mean a kind of effortless charm and beauty. Jansen’s language is graceful, and he offers forgiveness to the deeply flawed people in his past.